Testing and Verification of TLS

Introduction

TLS/SSL is the most widely adopted protocol for securing online communication. However, as we have seen in the past few weeks, creative attackers have found it riddled with exploitable weaknesses. Rather than just reacting to attacks as they are discovered, many projects instead proactively seek out potential security flaws to implement remedies before vulnerabilities are exploited. This is done primarily by testing and verification, the topic of this week’s blog post.

First, we will examine some motivating attacks on TLS implementations, including the Heartbleed attack, CRIME attack, and the infamous “goto fail”, as well as their solutions. Next, we will discuss differential testing, a technique that creates well-formed but forged certificates, called “frankencerts”, and uses them to compare the responses of many popular implementations such as OpenSSL - and how they strengthened their defenses afterward (or didn’t). Finally, we introduce verification, which takes advantage of the relationship between computer systems and mathematics to rigorously prove properties about programs, either by type-checking existing programs or building a program from scratch starting with abstract refinement types.

Heartbleed

Heartbleed by Codenomicon (2014)

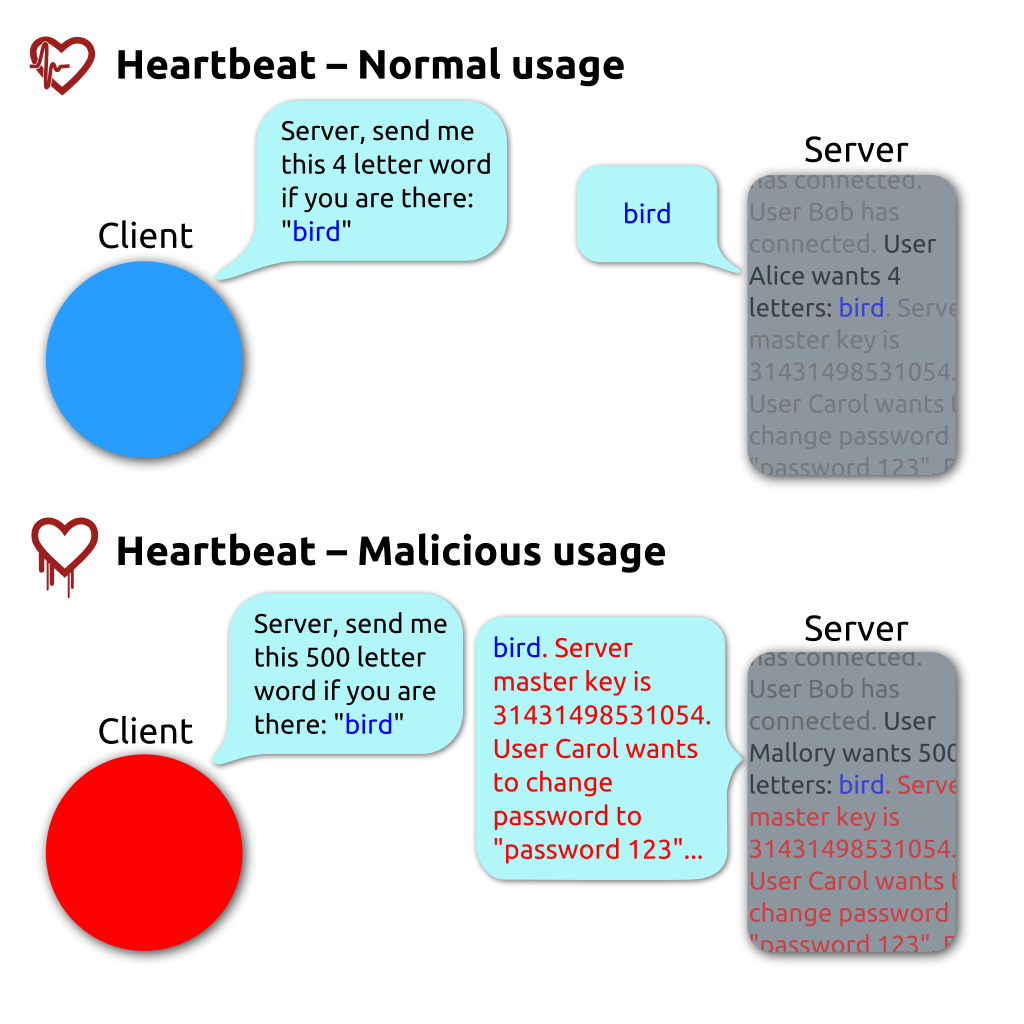

OpenSSL’s heartbleed bug exploits heartbeat requests between a client and a server. In the OpenSSL implementation, the client does not check the actual lengths of the message but trusts the length field in the request message. If the real message is shorter than the length specified in the length field, then the payload returned in the response heartbleed can also contain what happened to be in the allocated memory buffer. In this manner, secret keys, login credentials, sensitive data, and miscellaneous memory are all at risk of exposure.

Source: Wikipedia

Compression Ratio Info-Leak Mass Exploitation (CRIME)

The CRIME Attack by Juliano Rizzo and Thai Duong (2013)

CRIME attacks were developed by Juliano Rizzo and Thai Duong in 2012 and exploited TLS Compression by injecting plaintext into victim’s web requests and observing the outcome length. Tampering with web requests is made possible by injecting malicious JavaScript code through a network attack. Through many trials, the attacker can steal user cookies and hijack the session.

Source: Infosec Institute

Goto Fail;

Understanding Apple ‘goto fail’ Vulnerability by Amit Sethi (2014)

In February 2014, Apple released a security update on many versions of its operating system that included the following vulnerability in the function SSLVerifySignedServerKeyExchange.

if ((err = SSLHashSHA1.update(&hashCtx, &signedParams)) != 0)

goto fail;

goto fail;

… other checks …

fail:

… buffer frees (cleanups) …

return err;

The indentation on the second goto fail; is misleading. The lack of curly brackets meant that the second goto fail; will always be executed, skipping vital signature checking and accepting both good and bad signatures.

Differential Testing

Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate Validation by Chad Brubaker, Suman Jana, Baishakhi Ray, Sarfraz Khurshid, and Vitaly Shmatikov (2014)

An empirical study of goto in C code from GitHub repositories by Meiyappan Nagappan, Romain Robbes, Yasutaka Kamei, Éric Tanter, Shane McIntosh, Audris Mockus, and Ahmed E. Hassan (2015)

Differential testing is the process of searching for bugs in software by running multiple programs on the same inputs. If there is a discrepancy between one program’s results on a given input and another’s, it’s likely that one of the implementations is bugged. A differential testing system will flag such results for human review.

Brubaker et al. used this technique to test server authentication for many implementations of SSL/TLS as presented in their 2014 “Frankencerts” paper. The researchers initially had to deal with the dual problems of generating test case certificates and successfully interpreting the results of acceptance and rejection.

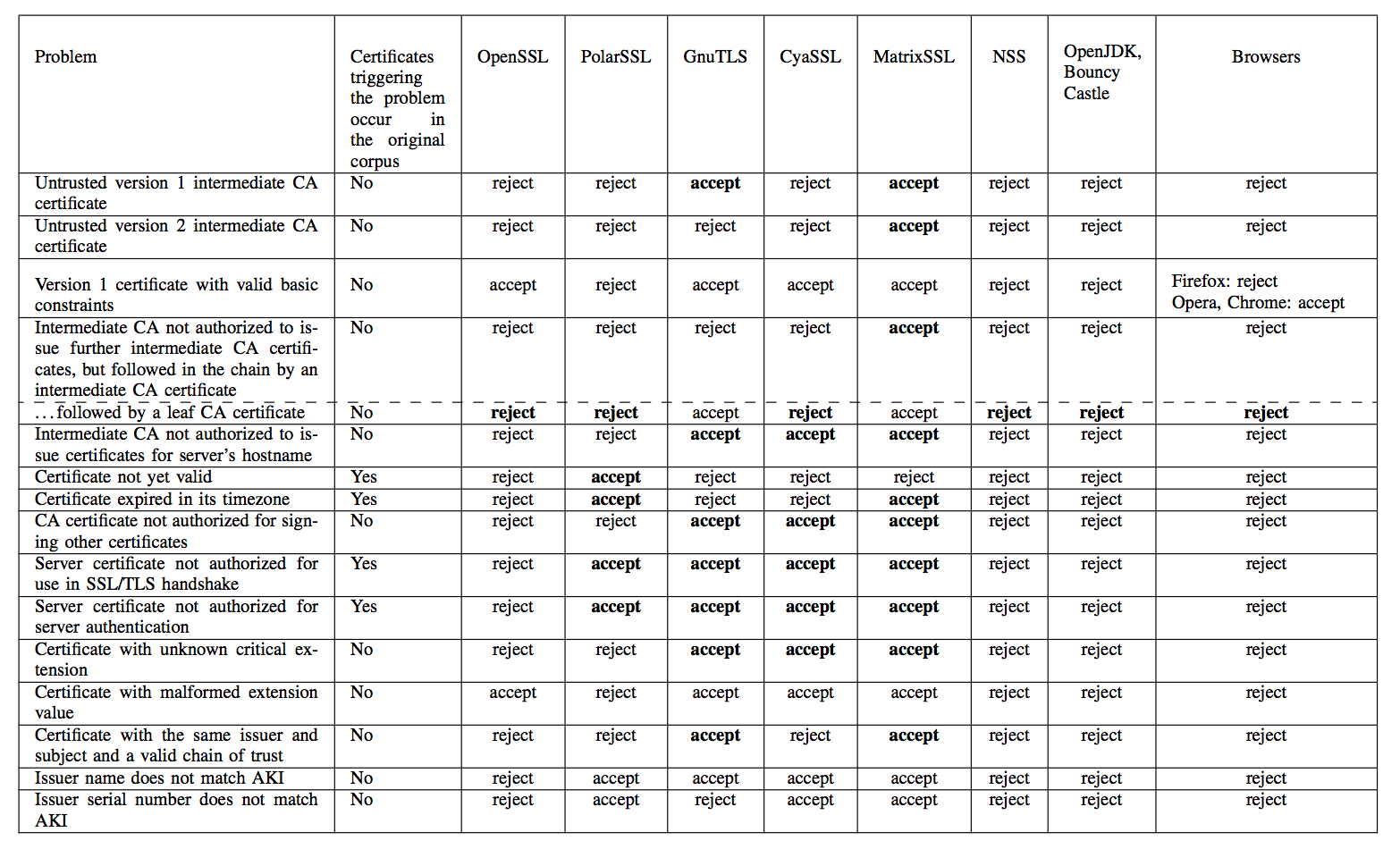

Generating certificates proved to be a challenge due to the nature of an SSL certificate. Simply randomly fuzzing valid certificates is unlikely to produce data parsable as a certificate. Manually creating test cases would take too long and potentially miss edge cases that a more statistically comprehensive generation method would find. The researchers decided on creating frankencerts by scanning 243,246 current certificates from the internet and randomly permuting their parts. This process guaranteed that the 8,127,600 frankencerts would be parsable as certificates and resulted in a wide variety of unusual combinations of extensions, key usage constraints, odd CAs, and other possible variations within a cert.

The researchers then ran OpenSSL, NSS, GnuTLS, CyaSSL, PolarSSL, MatrixSSL, OpenJDK, and Bouncy Castle on the frankencerts, looking for discrepancies between results. Because each of these libraries is intended to implement the same X.509 certificate validation logic, any discrepancy in certificate acceptance between them would indicate that SOMEONE was screwing up. Thus the researchers dealt with the second issue, that of interpreting the results of their tests.

Running the differential test on all 8 million frankencerts and the quarter-million real certificates produced 208 discrepancies that, when manually investigated, uncovered many serious flaws in the various implementations (error results are bolded):

Source: Chad Brubaker, Suman Jana, Baishakhi Ray, Sarfraz Khurshid, and Vitaly Shmatikov

Any of the invalid acceptances would allow for an in-the-middle attack to be crafted against the implementation in question. The researchers contacted the developers of the various SSL/TLS implementations affected and reported their results before publishing, allowing the developers time to fix their bugs.

Chen and Su’s mucert builds on the frankencert method. Mucerts are randomly fuzzed test certificates generated from a seed set of certificates. The fuzzing, or mutating, occurs in accordance with a number of guidelines that prevent mutations from generating unparseable certificates. Chen and Su statistically evaluated mucerts and compared them to frankencerts, finding that mucerts attained drastically higher levels of corner case coverage.

Verification

Verifying s2n HMAC with SAW by Joey Dodds (2016)

Implementing TLS with Verified Cryptographic Security by Karthikeyan Bhargavan, Cédric Fournet, Markulf Kohlweiss, Alfredo Pironti,and Pierre-Yves Strub (2013)

Software Foundations by Benjamin C. Pierce, et al. (2017)

Software testing can only assert properties about program behaviors covered in the test suite. There will always be missed edge cases and odd bugs that will show up in code. This is where we turn to formal specifications to ‘prove’ the correctness of our code.

But how do we go about ‘proving’ this correctness? Let’s look at what we’re trying to solve in the first case:

For each behavior X in code, formally prove that X does what it should and nothing else. For those that are familiar with proofs and mathematical abstractions, this is known as a non-existence proof. In formal verification, we must prove that a program satisfies a formal specification of its behavior. By using the methods of mathematics, we can make strong statements regarding the correctness of our cryptographic implementations, for example, TLS.

To get down to formal verification, we must first define the difference between verification and validation. Validation asks questions like Does it meet the requirements?, Is it the right product?, and Does it function according to design?. Whereas, verification asks the question does this software meet a given specification under given assumptions?.

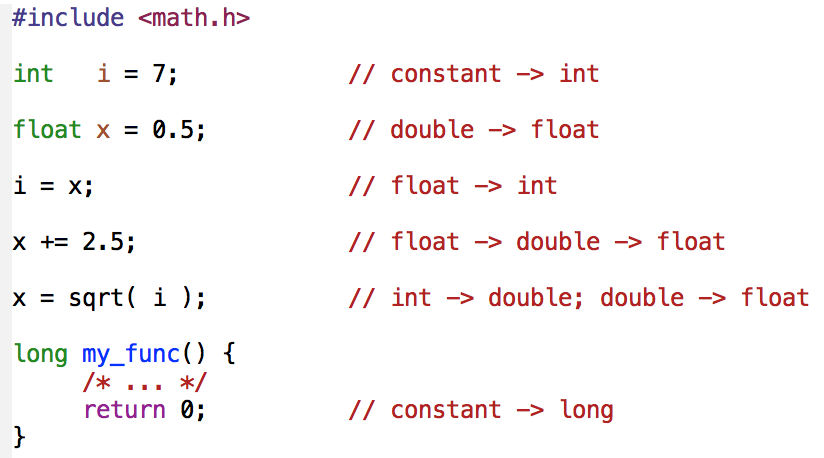

One requirement for nearly any stronger property is to first show the code satisfied type safety. A program is considered type safe if and only if the only operations that can be performed on data are those sanctioned by the type of data. For example, we can look at the following program where integers, floats, and doubles are being implicitly cast amongst one another. In a type safe program, an integer could never be treated as a float (more importantly, a pointer type would never be treated as a non-pointer, and vice versa).

While the below program is well-typed, it illustrates some of the challenges faced when attempting to show type safety for typical C code:

There are a variety of formal concepts that are used in program verification including model checking, deductive verification, equivalence checking, theorem proving, and correctness by construction. The problem that arises, though, is that some of these rely on concepts that simply are not feasible in commercial-level programs. For example, model checking exhaustively checks whether a model of the program meets a given specification, but every behavior in the program must have proper transitions and states resulting in the state explosion problem. Put simply, as more behaviors are added to simple programs, the number of states in the model exponentially grows. Due to this, it is challenging to scale model checking to large systems, although extensive work has been done toward this goal and often complex programs can be abstracted in ways that enable useful model checking.

One popular approach to verification is to use expressive type systems. Using the Curry-Howard isomorphism, we are able to directly relate programs with mathematical proofs and therefore have the ability to create refinement types which are types endowed with a predicate which is assumed to hold for any element of the refined type. What this means is that we can define our program using refinement types to encode the safety properties of the system which can be type-checked and proven to hold that safety property true.

There’s a lot that can be done with formal verification and TLS is a great possible use for fixing errors created during implementation. There are actually a number of projects for verifying parts of TLS out there that are attempting to combine together to formally verify TLS as a whole. This joint project is known as Project Everest. Everest is a pretty lofty goal considering the difficulty of formally verifying even small-level programs and scripts, but has made considerable progress towards building a fully verified TLS implementation. The eventual goal of Everest is that when all the projects are combined together, they will generate a C library that not only implements TLS 1.3 but is also proven secure, essentially circumventing any possible flaws in the TLS protocol.

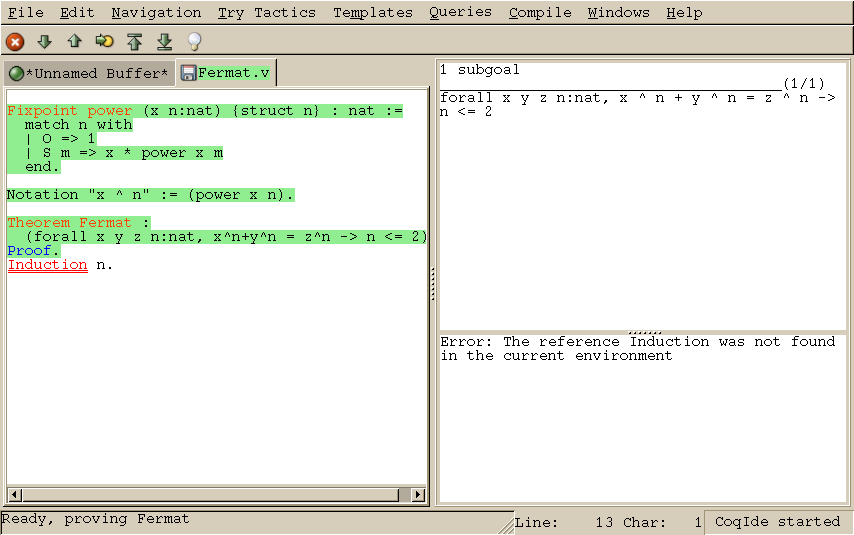

Coq

Team Cinnamon displayed a formal verification software called Coq during class. Coq is an assistive tool for the verification of code. The software implements a variety of mathematical and computational strategies to work, in combination with the user, to formally verify code, functions, and theorems. In class we ran through a couple of sample proofs to display the functionality and potential of Coq as a verification software and to give an example of how a formal verification software works.

A download for Coq is available at https://coq.inria.fr/ which offers different versions for different architectures. We used the CoqIDE which allows for editing Coq files with helpful syntax highlighting and is useful when trying to first learn Coq. For a good introduction to Coq, as well as number of exercises for what to do, a group at UPenn has a great lab focused on Coq.

Source: The Coq Proof Assistant

Coq is extremely powerful software to help formally verify computer programs, but it can be difficult to learn, requiring a change in mentality for most programmers. For any problems or difficulties found when using Coq, there is plenty of documentation available within Coq’s Reference Manual.

Conclusion

Implementing cryptographic protocols correctly remains a huge challenge. There are tools available now that can prove interesting properties about software, including even the absence of certain types of side channels. It is important to remember, though, that anything we prove about a program is a proof about a property based on a model of the execution environment, and assumptions about adversary capabilities. As verification and testing tools get more sophisticated, those models can come increasingly close to the actual environment and capabilities of real adversaries, but today, there remains a large gap.