Downgrade Attacks

Last week we learned about Padding Oracle Attacks which use side-channel information related to ciphertext message padding in order to deduce the underlying plaintext message in a TLS communication. This week we will learn about Downgrade Attacks that force a TLS server to choose weaker encryption and protocol suit thereby making it vulnerable to attacks like man-in-the-middle.

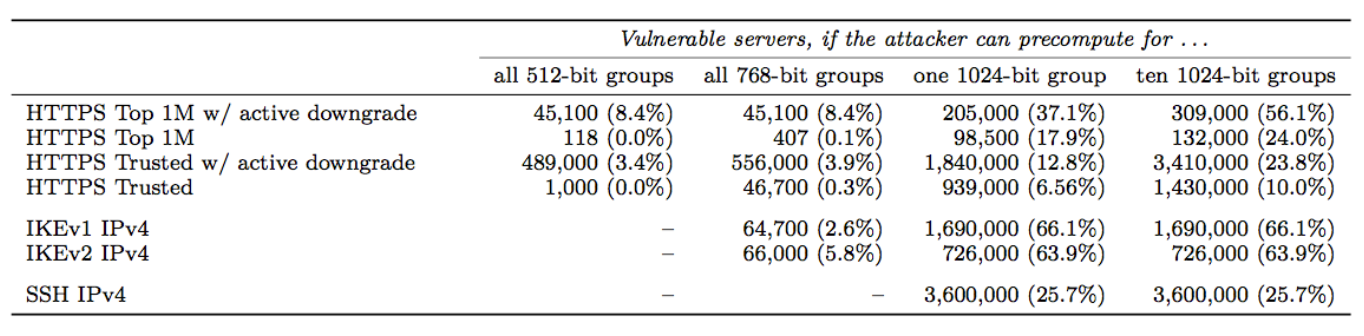

We begin with a brief introduction of Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange protocol commonly used in TLS and then describe the Logjam attack on Diffie-Hellman protocol which relies on pre-computation of discrete-logs of a 512-bit prime used in the protocol. Next we discuss about State-level Threats to Diffie-Hellman, where we show that the pre-computation of discrete-logs is in the reach of current academic computation power. The practical consequence is that 8% of the top 1 million websites that use HTTPS can be broken in real time.

In the remainder of the article, we discuss about Bleichenbacher Attack which is a padding oracle attack on PKCS#1 v1.5 padding used in SSLv2. We conclude with Drown Attack that uses Bleichenbacker attack to gain access to RSA key of a TLS communication.

Diffie-Hellman Cryptanalysis

Diffie-Hellman is a cryptologic method used to confidentially generate a shared secret (encryption key) between two parties in a conversation. Because the shared secret is used to encrypt message traffic, the integrity of Diffie-Hellman is crucial to the security of TLS, where the confidentiality of communication depends heavily on the process of securely generating a shared encryption key.

Background: Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

The genius of Diffie-Hellman lies in its adherence to the principle of perfect forward secrecy. The asymmetric keys used to perform the key exchange can be deleted after the key exchange is completed, so there is no risk of a later compromise enabling an attacker to break previous traffic. The agreed shared key is never transmitted, saved, or otherwise made observable across a communication channel, even if the adversary were to collect all encrypted data in transit and recover all material stored at the endpoints, it would still not be able to break the encryption.

The mathematical underpinnings of Diffie-Hellman are relatively simple. See the following image for an illustration of the exchange that occurs when generating a shared secret. Note that the secret values, a and b, are never transmitted nor shared between Alice and Bob.

The Diffie-Hellman Problem

The Diffie-Hellman problem (DHP) is as follows: Given an element \(g\) and the values \(g^x, g^y\) what is the value of \(g^{xy}\)?

Clearly, if this problem were easy to solve, Diffie-Hellman would be useless, since any eavesdropping adversary could then collect both \(g^x\) and \(g^y\), compute \(g^{xy}\), and subsequently decrypt all of Alice and Bob’s communication. The Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP) is thus by far the most efficient means to solve DHP and requires that the eavesdropping adversary compute \(x\) given \(g\) and \(g^x\) – still believed to be a hard problem in general. But, if \(p\) is a weak prime (as explained below), it can solved in a reasonable amount of time with available computing resources.

Adrian et al. published a paper in 2015 that demonstrated a weakness in Diffie-Hellman key exchange in the Handshake Protocol of TLS. In order to perform cryptanalysis in such a situation, an attacker must solve DLP by computing arbitrary discrete log values in real-time. While it is not known how to calculate discrete logs efficiently (and believed to be hard), the attack can be accelerated using precomputation.

Index Calculus

While the logic behind the precomputation cryptanalysis is based on the General Number Field Sieve, we examine Index Calculus, a simplified version of the same concept. Index Calculus involves two steps: sieving and linear algebra. In the sieving step, the cryptanalyst chooses a multiplicative group of numbers and attempts to find numbers that factor completely over this group. We can then express these numbers as linear combinations of logs of the multiplicative group elements. By finding many such numbers, we obtain equations in terms of logs of multiplicative group elements. In the linear algebra step, we can use these equations to solve for values of the logs. This allows us to generate a database of precomputed logs.

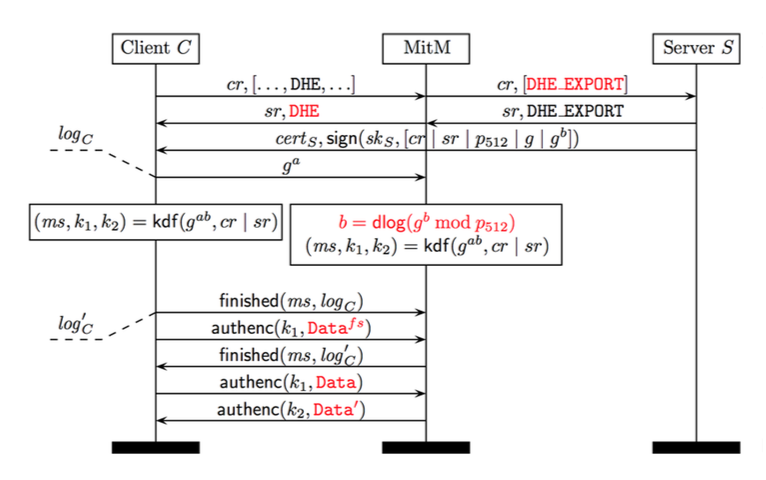

Active Downgrade

Using precomputed discrete logs, an attacker can perform an active downgrade attack on a TLS connection. Operating as an in-the-middle attacker, the attacker intercepts a Client Hello message and alters it to instruct the server to use export-grade Diffie-Hellman, which uses 512-bit keys rather than 1024-bit or higher, which allows the attacker to use the precomputed logs. During the Handshake Protocol, the attacker is able to solve the discrete log problem and recover the master secret of that connection. This allows the attacker to communicate directly with the client over an encrypted channel, while the client still thinks he/she is communicating with their intended server.

The Logjam Attack: Step-by-Step

The Client sends a

Client Hellomessage to the Server. This includes a list of all supported ciphersuites that can be used to generate the shared secret and requests that one be selected by the Server to begin the Diffie-Hellman exchange.The adversary intercepts the

Client Hellomessages and alters the available ciphersuites to only include 512-bit Diffie-Hellman, then forwards the altered Client Hello to the Server.The Server receives the

Client Hello. Since only one ciphersuite is shown to be supported by the Client, the Server agrees to 512-bit Diffie-Hellman and generates a 512-bit prime \(p\) to be used in the key exchange.The adversary intercepts the ciphersuite confirmation message from the Server and alters it to reflect the client’s original ciphersuite preference, selecting full-strength DHE. It also eavesdrops on the Server’s Diffie-Hellman communication to discern \(g\) and \(gb\).

The Client thinks it has received the proper Diffie-Hellman information from the Server and begins its half of the Diffie-Hellman exchange. Note that the 512-bit prime \(p\) is still considered a valid prime for 1024-bit DHE. Meanwhile, the adversary is hard at work calculating the discrete log of \(g^b \mod p_{512}\). Multiple factors can contribute to reduce the time-complexity of this process.

Once the adversary has determined the value of \(b\), the Client and adversary begin communicating as though the adversary is the Server.

The time-complexity of precomputation using the number field sieve is entirely dependent on the prime number used; as a result, any connections using the same prime can be quickly broken. The researchers behind Logjam detected that millions of HTTPS, SSH, and VPN servers use the same prime numbers for Diffie-Hellman key exchange, rendering supposedly-secure communications vulnerable to Logjam.

Weak Primes

Consider a prime number \(p\). In 1978, Pohlig and Hellman demonstrated that if all factors of \(p-1\) are less than \(\log^c p\), the problem of solving the discrete logarithm \(\mod p\) is in \(P\). In general terms, this means an attacker can greatly reduce the complexity of the discrete logarithm problem and thus conduct the Logjam attack in a shorter period of time. We’ll demonstrate with an example using a small prime.

Let \(p = 31\) and \(g = 3\). \(g\) has order 30 → \(g^{30} = 1 \mod p\)

The factors of \(30 = 2 * 3 * 5\) are too small for the prime \(p\) to be secure, allowing an attacker to convert the discrete logarithm problem \(\mod 31\) into problems \(\mod 2, 3, 5\). With the help of the Chinese Remainder Theorem, an attacker can easily find \(x\) given \(g\) and \(g^x\).

A strong prime \(p = 2q + 1\) (\(q\) is prime) avoids this problem of reducibility by ensuring that \((p-1)\div 2\) cannot be composite (and, by extension, that Pohlig-Hellman cannot obtain information from \(p\)).

This puts a server that supports export-grade DH and reuses weak primes at severe risk to a motivated attack.

State-Level Threats to Diffie-Hellman

Current Situation

In recent years, the general bar for internet security has raised substantially. HTTPS is now the norm for most heavily trafficked websites and is spreading through services such as Let’s Encrypt, that allow for domain owners to easily get SSL certificates for a website at no cost. In general, this trend looks positive: for key exchange protocols, stronger 768 and 1024-bit groups are now the norm rather than the exception. Individual users and institutions have also begun to better understand the need for security and IPSec Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and SSH connects are being more broadly practiced.

Academic Power

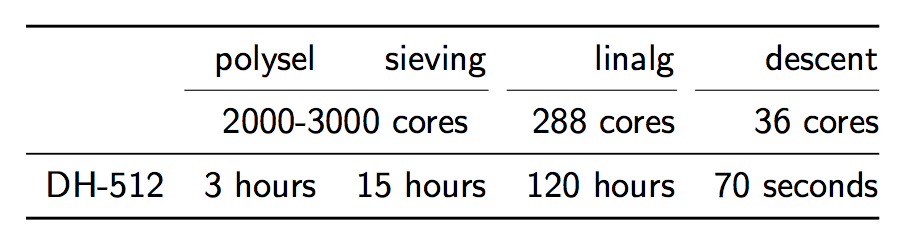

While standards have advanced and security has increased in general, cryptanalysis techniques and computational power have also increased. Although ideas such as Moore’s Law, that computing power at a certain price level effectively doubles every 18 months, the practical implications are not as often taken into account. These days, DH-512 is easily within the reach of “academic power,” that is to say, within the reach of institutions with access to midsize computing facilities or individuals who can afford a few hundred thousand dollars of computing.

With recent hardware, to “crack” DH-512 takes 2.5 core-years in the sieving phase, 7.7 core-years in the linear algebra phase, but only 10 core-minutes in the descent phase. So, given a 2000-3000 core cluster, all of the phases combined except the descent phase takes about 140 hours.

https://weakdh.org/weakdh-ccs-slides.pdf>

However, the descent phase only takes about 70 seconds. What does this mean? That after 1 week of pre-computation, an individual calculation can be completed in about 70s. If this is combined with something called a “downgrade attack,” which will be described below, connections to about 8% of top 1 million sites that use HTTPS can be broken in real time.

Sidebar: What’s a Core Year?

A “core-year” is a measure of the amount of work that an average computer core can complete in a year. To give a point of reference in terms of concrete cost, a single-core Amazon EC2 instance costs about $0.02 / hours. To run that core for a year would cost about $0.02 * (24 *365) = $175. A core-day and a core-minute are defined similarly.

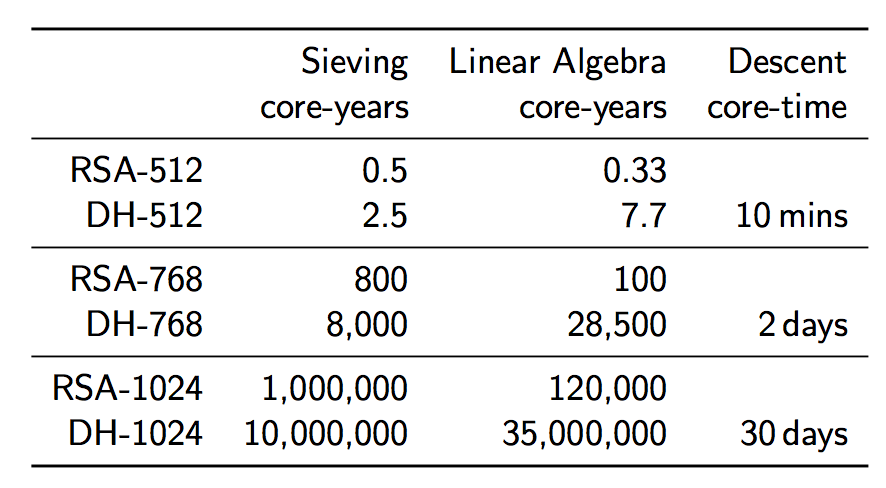

Although it may seem like this isn’t as serious of a problem, since current practice is usually to use DH-768 or DH-1024 –for example, 91.0% of IKEv2 servers support a 1024-bit connection– in actuality even those are vulnerable to attack. In 2009, a new record was achieved for integer factorization with a 768 bit integer factorization completed with academic resources over the span of 2 years. This would imply that breaking DH-768 takes about 36,500 core-years in pre-computation and 2 core-days in decent. As much as this sounds, it is only a few million dollars worth, which is well within reach of both moderately-funded academics and moderately-motivated adversaries (and peanuts for an organization like the NSA).

Structural Costs

Ok, so a DH-768 connection can probably be broken by a non-state-level actor, but what about a DH-1024 connection? Surely that is ok? Let’s take a look at the costliness of DH-1024 in comparison to 768-bit DH. The algorithmic time complexity increases by a factor of about 1220, the space complexity by a factor of 95, leaving us with this:

https://weakdh.org/weakdh-ccs-slides.pdf

Although the costs seem astronomically high, they are actually within the reach of a state-level actor. If we assume that some special purpose ASICs are developed to help speed up the sieving pre-computation such that it can be completed in one year (this would cost around $8 million), and we get access to, say, a Titan supercomputer for one year (at a cost of $122 million) to complete the linear algebra phase in one year, we find that we can complete all of our pre-computation for the small cost of $130 million dollars. Compare this cost to the budget of a state-level actor such as the NSA: their 2012 budget was $10.5 billion, making this computation just 1% of that budget.

What’s so Good About Breaking One Group?

But, you might object, what is the value in doing this pre-computation and breaking one group? Doesn’t this just mean that the NSA can only break a couple connections per year? Unfortunately, no. As Edward Snowden said, “If performing number field sieve pre-computations for at least a small number of 1024-bit Diffie-Hellman groups is possible, breaking any key exchanges made with those groups in close to real time is no difficulty.” This is because once the pre-computations are completed for a single group, that work can then be used to crack numerous connections.

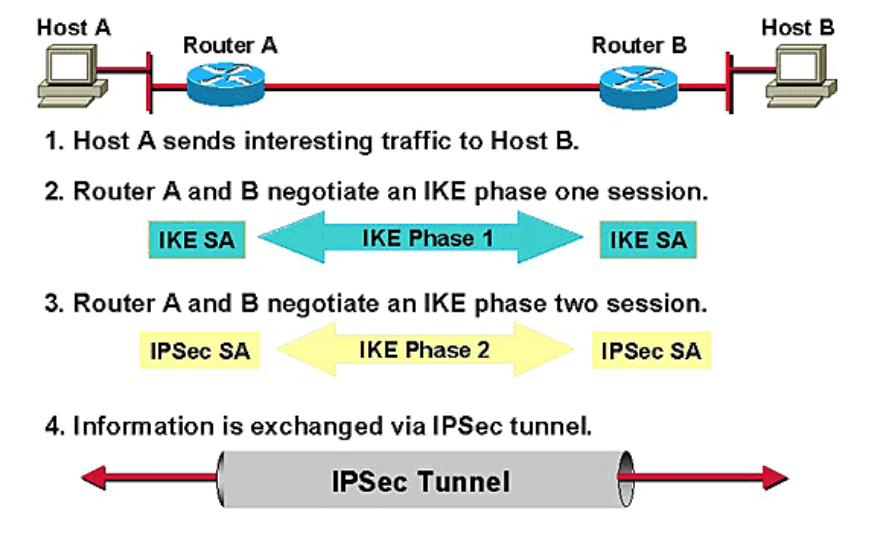

IKE (IPsec VPNs)

Let’s now take a step back and look at IKE, the Internet Key Exchange, which perhaps is the most vulnerable to these kinds of attacks. IKE is a protocol used, in the IPsec protocol, to create a “Security Association (SA),” which is just a set of shared security attributes between two network parties such as cryptographic algorithm being used, the algorithm mode, credentials, etc. In order to establish the SA, two parties go through a process like this:

https://weakdh.org/weakdh-ccs-slides.pdf

While the exact details of how the protocol works are not important, it is important to note that to perform IKE passive decryption, an adversary would have to have access to a known pre-shared key, both sides of the IKE handshake, and both the handshake traffic and ESP traffic.

Also important to note is that the vast majority of IKE systems use one particular 1024-bit DH group, the Oakley Group 2, for the protocol. We find that 86.1% of IKEv1 servers and 91.0% of IKEv2 servers support Oakley Group 2, and 66.1% of IKEv1 servers and 63.9% of IKEv2 servers chose Oakley Group 2 for the protocol. This means that a state-level actor with access to the pre-shared key, both sides of the IKE handshake, and both the handshake traffic and ESP traffic would be able to passively decrypt 66% of VPN server traffic…in near real-time.

Show me the Adversary

Is this all hypothetical? Does any such adversary actually exist?

A 2012 Wired article revealed information that the NSA, several years before 2012, made an “enormous breakthrough” in its ability to cryptanalyze current public encryption. While the exact details are not known, it may be reasonable to assume that the NSA completed the pre-computation for a 1024-bit DH group, such as the Oakley Group 2, allowing them passive decrypted access to a swath of internet traffic.

https://weakdh.org/weakdh-ccs-slides.pdf

https://weakdh.org/weakdh-ccs-slides.pdfThe impact of such a break to IKE has already been noted. Other protocols would also be vulnerable to the break. SSH, for example, supports Oakley Group 2, Oakley Group 14, or a server-defined group that is negotiated through a DH-GEX handshake. According to recent data, 21.8% of servers prefer Oakley Group 2, and 37.4% prefer the server-defined group. However, of that 37.4%, almost all of them just provided Oakley Group 2 rather than a real custom group. Thus, a state-level attacker that performed the break could passively eavesdrop on connections to 25.7% of all publicly accessible SSH servers.

Unfortunately, HTTPS connections are similarly affected. Of the top 1 million site that support DHE, 84% use a 1024-bit or smaller group, and 94% of those use one of five common groups. Thus, 17.9% of connections to the top 1 million sites could be passively eavesdropped with the pre-computation for a single 1024-bit prime.

Mitigations

Is there any hope that a connection can really be secure given this information? Luckily, some mitigations can be put into place. First, servers can move to using elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). A transition to a elliptic curve Diffe-Hellman key exchange (ECDH) with appropriate parameters would thwart all known feasible cryptanalytic attacks as ECC discrete log algorithms don’t gain too much advantage from precomputation. When ECC is not an option, it is recommended that primes at least 2048 bits in length be used. It would be ideal if browser vendors and clients raise the minimum accepted size for DH groups to at least 1024 bits. If large primes are not supported, then always use a fresh 1024-bit group to mitigate the efficacy of precomputation-based attacks. It is parameter reuse that allows state-level attackers to easily perform wide-scale passive decryption.

Bleichenbacher’s Padding Oracle Attack

Bleichenbacher’s padding oracle attack is an adaptive chosen ciphertext attack against PKCS#1 v1.5, the RSA padding standard used in SSL and TLS. It enables decryption of RSA ciphertexts if a server distinguishes between correctly and incorrectly padded RSA plaintexts, and was termed the “million-message attack” upon its introduction in 1998, after the number of decryption queries needed to deduce a plaintext. All widely used SSL/TLS servers include countermeasures against Bleichenbacher attacks.

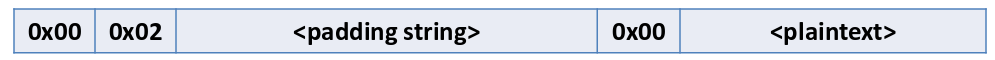

PKCS#1 v1.5 encryption padding

Bleichenbacher’s padding oracle attack relies on the structure of RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 padding. Although RSA PKCS#1 v2.0 implements OAEP, SSL/TLS still uses PKCS#1 v1.5. The PKCS#1 v1.5 encryption padding scheme randomizes encryptions by prepending a random padding string PS to a message k (here, a symmetric session key) before RSA encryption:

The plaintext message is k, \(l_k = |k|\). The encrypter generates a random byte string PS, where |PS| ≥ 8, \(|PS| = l_m − 3 − l_k \) and

0x00\( \notin{PS[1],…,PS[|PS|]}\)The encryption block is \(m =\)

00||02|| \(PS\) ||00|| \(k\)The ciphertext is computed as \(c = m^e\mod{N}\). To decrypt such a ciphertext, the decrypter first computes \(m = c^d \mod{N}\). Then it checks whether the decrypted message m is correctly formatted as a PKCS#1 v1.5-encoded message. We say that the ciphertext c and the decrypted message bytes \(m[1]||m[2]||…||m[l_m]\) are PKCS#1 v1.5 conformant if:

\( \qquad m[1] || m[2] = \)

0x00||0x02and0x00\(\notin {m[3],…,m[10]} \)If this condition holds, the decrypter searches for the first value i > 10 such that \(m[i] =\)

0x00. Then, it extracts \(k = m[i+1]||…||m[l_m]\). Otherwise, the ciphertext is rejected.

In SSLv3 and TLS, RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 is used to encapsulate the premaster secret exchanged during the handshake. Thus, k is interpreted as the premaster secret. In SSLv2, RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 is used for encapsulation of an equivalent key denoted the master_key.

Bleichenbacher attack

Bleichenbacher’s attack is a padding oracle attack; it exploits the fact that RSA ciphertexts should decrypt to PKCS#1 v1.5-compliant plaintexts. If an implementation receives an RSA ciphertext that decrypts to an invalid PKCS#1 v1.5 plaintext, it might naturally leak this information via an error message, by closing the connection, or by taking longer to process the error condition. This behavior can leak information about the plaintext that can be modeled as a cryptographic oracle for the decryption process. Bleichenbacher demonstrated how such an oracle could be exploited to decrypt RSA ciphertexts.

Algorithm

In the simplest attack scenario, the attacker has a valid PKCS#1 v1.5 ciphertext \(c_0\) that they wish to decrypt to discover the message m0. They have no access to the private RSA key, but instead have access to an oracle, \(\delta\), that will decrypt a ciphertext c and inform the attacker whether the most significant two bytes match the required value for a correct PKCS#1 v1.5 padding:

0x00~02 0

$$ \delta (c) = 0 \textrm{ otherwise}.$$

The attacker can take advantage of RSA malleability to generate new candidate ciphertexts for any s:

$$c = (c_0 · s_e)\mod{N} = {m_0 ·s}^e \mod{N}$$

The attacker queries the oracle with c. If the oracle responds with 0, the attacker increments s and repeats the previous step. Otherwise, the attacker learns that for some r, \(2B ≤ m_{0}s−rN < 3B\). This allows the attacker to reduce the range of possible solutions to:

$$ \frac{2B+rN}{s} ≤ m_0 < \frac{3B+rN}{s} $$

The attacker proceeds by refining guesses for s and r values and successively decreasing the size of the interval containing \(m_0\). At some point the interval will contain a single valid value, \(m_0\). Bleichenbacher’s original paper describes this process in further detail.

It is worth noting that the author implemented a proof-of-concept of this attack on a custom padding oracle implementation. Over a test set of various 512-bit and 1024-bit keys, between 300,000 and 2 million ciphertexts were required to find the message. While the details of the custom oracle are not known, it is reasonable to assume that this attack is feasible in more realistic scenarios.

Countermeasures

In order to protect against this attack, the reciever must not leak information about the PKCS#1 v1.5 validity of the ciphertext. The ciphertext does not decrypt to a valid message, so the decrypter generates a fake plaintext and continues the protocol with this decoy. The attacker should not be able to distinguish the resulting computation from a correctly decrypted ciphertext. In the case of SSL/TLS, the server generates a random premaster secret to continue the handshake if the decrypted ciphertext is invalid. The client will not possess the session key to send a valid ClientFinished message and the connection will terminate.

In addition, newer versions of PKSC#1 describe a new padding type, called OAEP, which uses hash function to add more internal redundancy. This greatly decreases the probability that random strings will result in valid padding, effectively preventing the attack.

Sources of Further Reading

Cryptopals Crypto Challenge: A Do-It-Yourself excercise on Bleichenbacher attack.

Efficient padding oracle attacks on cryptographic hardware

DROWN: Breaking TLS using SSLv2

DROWN attack is inspired by Bleichenbacher’s padding oracle attack over SSLv2 which could decrypt an SSLv2 RSA ciphertext. The attack was possible due to a flaw in SSLv2 protocol which revealed if the decrypted message was conformant with PKCS#1 v1.5 padding or not, thus acting as a padding oracle. The padding scheme is shown below where first two bytes are fixed 0x00 0x02 followed by 8 bytes of random padding string succeeded by a 0x00 byte. The remaining part of the message is the plaintext which may contain the key to be recovered. The padding scheme is shown below:

PKCS#1 v1.5 Padding Scheme

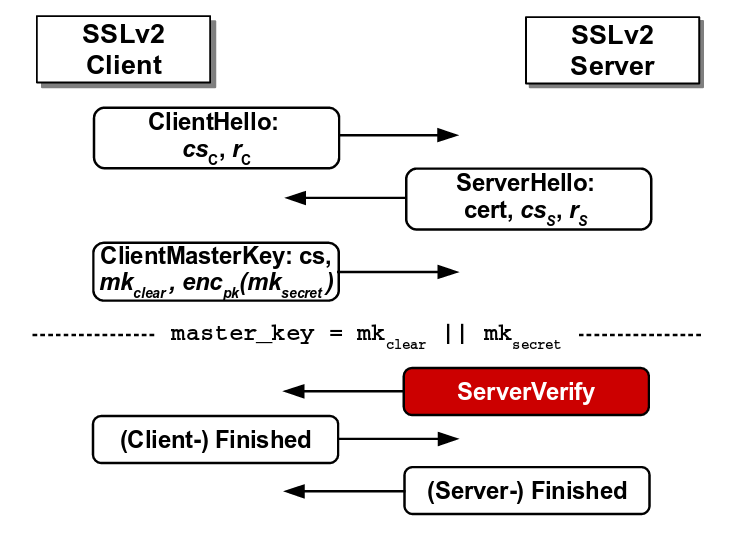

The client in SSLv2 protocol sends ClientMasterKey message to SSLv2 server which the server decrypts and responds with ServerVerify message which tells whether the ClientMasterKey message was conformant with the padding scheme.

The figure below depicts the SSLv2 protocol. The attacker can modify the original ClientMasterKey message and if the SSLv2 server confirms the padding, the attacker would immediately get to know that the first two bytes of the modified message is ‘0x00 0x02’. This way, the attacker can repeatedly modify the original message and query the oracle. After multiple successful guesses for modified message, the attacker can narrow down the guesses for the original message and recover the master_key.

Flaw in SSLv2 protocol where the server reveals the correctness of padding

Source: https://tlseminar.github.io/docs/drown.pdf

Moreover, SSLv2 allowed export-grade ciphersuites which supported 40-bit key. A Bleichenbacher attacker could brute-force the key by repeatedly querying the SSLv2 server.

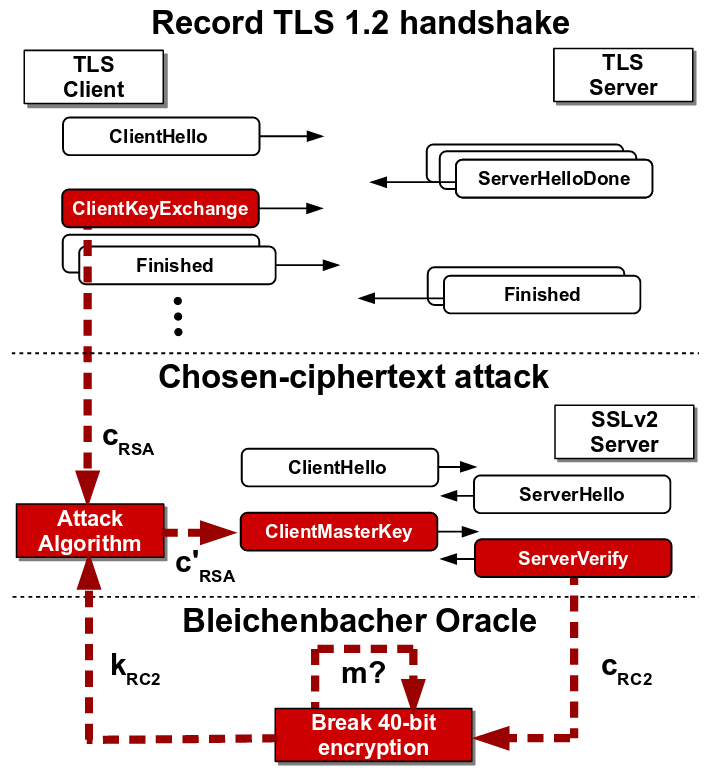

TLS patched the above flaws and (most) servers made the SSLv2 protocol obsolete. However, it was not uncommon for TLS servers to share same RSA keys with SSLv2 servers. This made the TLS servers vulnerable to a modified form of Bleichenbacher attack which uses a SSLv2 server as padding oracle to decrypt the shared RSA key. DROWN instantiated this protocol-level attack and decrypted a TLS 1.2 handshake using 2048-bit RSA in 8 hours at a cost of $440 on Amazon EC2. As if this wasn’t devastating enough, the authors of DROWN pointed out some implementation bugs in OpenSSL which lead to another attack called Special DROWN that could decrypt a TLS ciphertext in under 1 minute using a single CPU. Both the attacks are described below.

DROWN Attack

DROWN attack requires that a TLS server and a SSLv2 server share an RSA key. The attacker records multiple TLS handshake messages between a client and the TLS server. The aim of the attacker is to decrypt the RSA key of the TLS handshake. To do so, the attacker forces the client to establish a connection with an SSLv2 server having the same RSA key so that the attacker can initiate the Bleichenbacher attack to recover the RSA key.

Now the main hurdle for the attacker is that the format of TLS handshake message may not comply with PKCS#1 v1.5 padding scheme of SSLv2. The attacker converts the TLS ciphertext to SSLv2 ciphertext using the concept of trimmers introduced by Bardou et al. which reduces the size of the TLS message. The use of trimmers require repeated querying to SSLv2 server by shifting the message bytes. The recovered SSLv2 plaintext is then converted back to TLS plaintext which reveals the RSA key of TLS handshake.

SSLv2-based Bleichenbacher attack on TLS

Source: https://tlseminar.github.io/docs/drown.pdf

Special DROWN Attack

The OpenSSL implementation had two bugs which led to a more efficient Bleichenbacher attack on an OpenSSL implementation of SSLv2 server.

OpenSSL extra clear oracle: OpenSSL implementation allowed non-export cipher messages to contain clear_key_data which lead to potential overwriting of key bytes with null bytes. An attacker could vary the number of null bytes to decrypt the whole key one byte at a time.

OpenSSL leaky export oracle: OpenSSL in export cipher mode allowed valid oracle response for correctly padded message of ‘any’ length.

These bugs remained in OpenSSL implementation from 1998 up until its patch in 2015, when the authors of DROWN contacted the OpenSSL developers.

Prevention of DROWN

The attack is successful mainly because of the reliance on obsolete cryptographic practices. Export-grade ciphers only support 40-bit keys which are vulnerable to brute-force attack and hence it is crucial to disable export-grade ciphers and use safer ciphers (like AES_GCM) with longer key lengths (256-bits). PKCS#1 v1.5 padding leaks significant byte patterns and hence a better padding technique should be used. SSLv2 protocol includes the above obsolete cryptos and hence it should be scrapped and replaced with TLS 1.3. Lastly, the RSA public keys should not be shared among multiple servers or connections in order to deter the attack.