SHA-1 Collisions

The First SHA-1 Collision

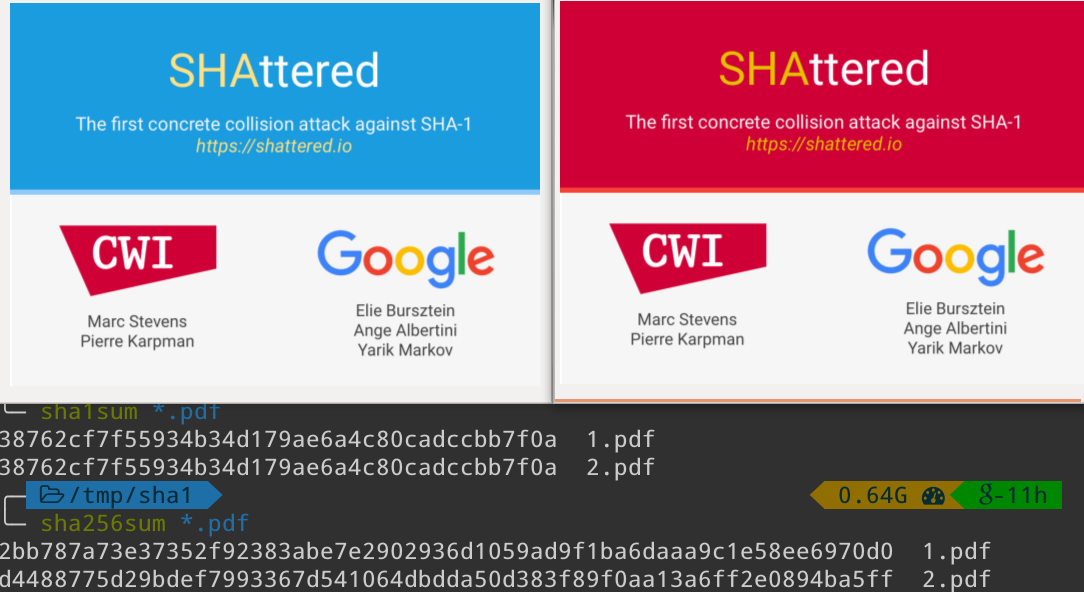

On February 23rd, 2017, researchers from Google and CWI Institute in Amsterdam) announced the first SHA-1 collision. As proof of this claim, two PDFs were published that yield the same SHA-1 hash despite containing different content (PDF 1, PDF 2).

https://shattered.it/static/shattered.png

While weaknesses in SHA-1 had been known since the work by Xiaoyun Wang and colleagues in 2004, this is the first known attack to find an actual SHA-1 collision. While SHA-1 was deprecated by NIST in 2011, many systems still extensively use SHA-1 (git, SVN, even some certificate authorities, etc.). The researchers argue that these findings should reinforce the need to more secure hashing algorithms:

We hope that our practical attack against SHA-1 will finally convince the industry that it is urgent to move to safer alternatives such as SHA-256.

Attack Details

SHA-1 takes an arbitrary length message and computes a 160-bit hash. It divides the (padded) input into \(k\) blocks \(M_1, M_2, …, M_k\) of 512 bits. The 160-bit internal state \(CV_j\), called the chaining value, is initialized to some initial value \(CV_0 = IV\). Then, each block \(M_j\) is fed to a compression function \(h\) that updates the chaining value, \(CV_{j+1} = h(CV_j, M_{j+1})\). \(CV_k\) Is the output of the hash.

The attack implements the best known theoretical collision attack outlined by Stevens (2013) (one of the leaders of this effort). This attack is an identical-prefix collision attack, where a given prefix \(P\) is extended with two distinct near collision block pairs such that they collide for any suffix \(S\):

$$ \text{SHA-1}(P||M_1^{(1)}||M_2^{(1)}||S) = \text{SHA-1}(P||M_1^{(2)}||M_2^{(2)}||S) $$

Finding both the first and second near collision block pairs, (\(M_1^{(1)}, M_1^{(2)}\)) and (\(M_2^{(1)}, M_2^{(2)}\)), respectively, was completed using slightly modified algorithms from Stevens’ work. Broadly speaking, differences in the first block pair cause a small difference in the output chaining value, which is “canceled” by the difference in the second block pair. The remaining identical suffixes ensure a collision. Differential paths are leveraged as a precise description of the differences in block pairs and how these differences evolve through the hashing steps. This description is the foundation of a search over the possible block pairs. Note that once the collision block pairs are found for a particular prefix, any number of colliding inputs can be found since S can be anything.

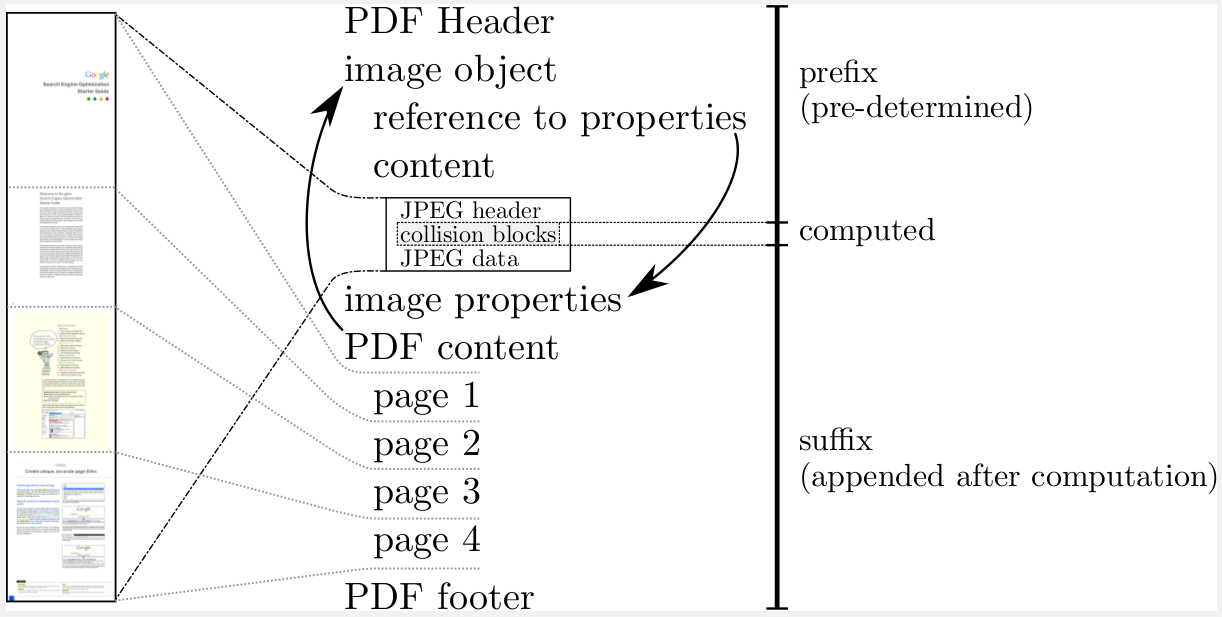

The PDF format is exploited by packaging the differing collision blocks into an embedded JPEG image. In the example collision, the differing blocks are aligned such that the background of the PDFs are different.

https://shattered.it/static/pdf_format.png

A significant contribution of this work is to apply these algorithms at the scale necessary for practical execution. While the source code for these computations has not yet been released (the authors are allowing a grace period to move to modern hashing algorithms), the changes required to scale this attack are highly non-trivial. Combined, the computations required approximately 6500 CPU years and 100 GPU years. At the time of publishing, the authors estimate the total cost of their attack (via AWS) at $110,000, easily within the reach of criminals. This attack is estimated to be approximately 100,000 times faster than a brute force search.

Full technical details of the attack are outlined in the released paper: Marc Stevens, Elie Bursztein, Pierre Karpman, Ange Albertini, Yarik Markov. The first collision for full SHA-1. (Released 23 February, 2017)