Padding Oracle Attacks

Introduction

Last week, we examined how the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol provides a private channel between two devices by following the handshake and record layers protocols. The handshake layer establishes a symmetric key that both the client and the server could use in the record layer to encrypt and decrypt messages.

This week, we’ll discuss a real-world TLS attack, the Padding Oracle Attack, that takes advantage of our need for each message to be a particular set length. If the original message is not long enough, then we have to add padding for the CBC Mode Encryption to work. Because the padding is present, an attacker can chip away information on the ciphertext, one byte at a time, through analyzing the receiver’s error messages for the sender, response time, and general behavior.

We’ll start out by learning about how CBC Mode Encryption works.

Padding and CBC Mode

Analysis of the SSL 3.0 Protocol by David Wagner and Bruce Schneider (1997)

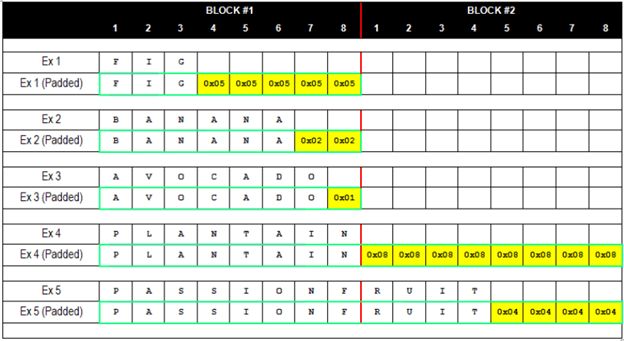

When AES-128 encryption is performed in cipher block chaining mode (CBC mode), the plaintext message is first split up into 16-byte (128-bit) blocks. It is often the case, however, that the length of the message is not perfectly divisible by 16. To account for varying message sizes, extra bytes, called padding, are concatenated after the end of the message to fill up the remaining quota for the final block.

These bytes are not chosen at random, however, and different cipher

modes prescribe different padding methods. In order to clearly mark

for the recipient where the message ends and the padding begins, the

padding follows a strict formatting pattern. With PKCS #5 padding as

used in TLS, if there are n bytes of padding, then each padding byte

contains the value n. For instance, if the last block contains 15

message bytes, the 1-byte padding contains 0x01; if the last block

contains 14 message bytes, the 2-byte padding contains 0x0202;

3-byte padding contains 0x030303; and so on.

Source: Gotham Digital Science

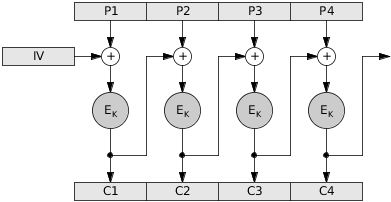

In CBC mode, the bytes of each plaintext block n are first XOR’ed with the encrypted bytes of the block before it, and their result is then encrypted. Block 1 is the obvious exception, which is XOR’ed with a fixed, random, or secret initialization vector (IV). Thus, for any block n > 1, where Ek is the encryption function, cn is the encrypted block n, pn is the plaintext block n, and cn-1 is the encrypted block n-1:

Source: Alan Kaminsky

However, the predictability of the padding format can turn out to be an extremely exploitable weakness for an active attacker. Under SSL/TLS protocol, when servers receive an encrypted message, their first step upon decryption is to check the validity of the padding; that is, determine if the numbers at the end of the last block represent the number of padding bytes. As soon as this step is completed, the server will return to the sender either an error code or an acknowledgment that the padding is valid. In this way, the server acts as an oracle to an active attacker, providing them with confirmations/rejections to inform their guesses.

Padding Oracle Attack

Security Flaws Induced by CBC Padding Applications to SSL, ISPEC, WTLS… by Serge Vaudenay

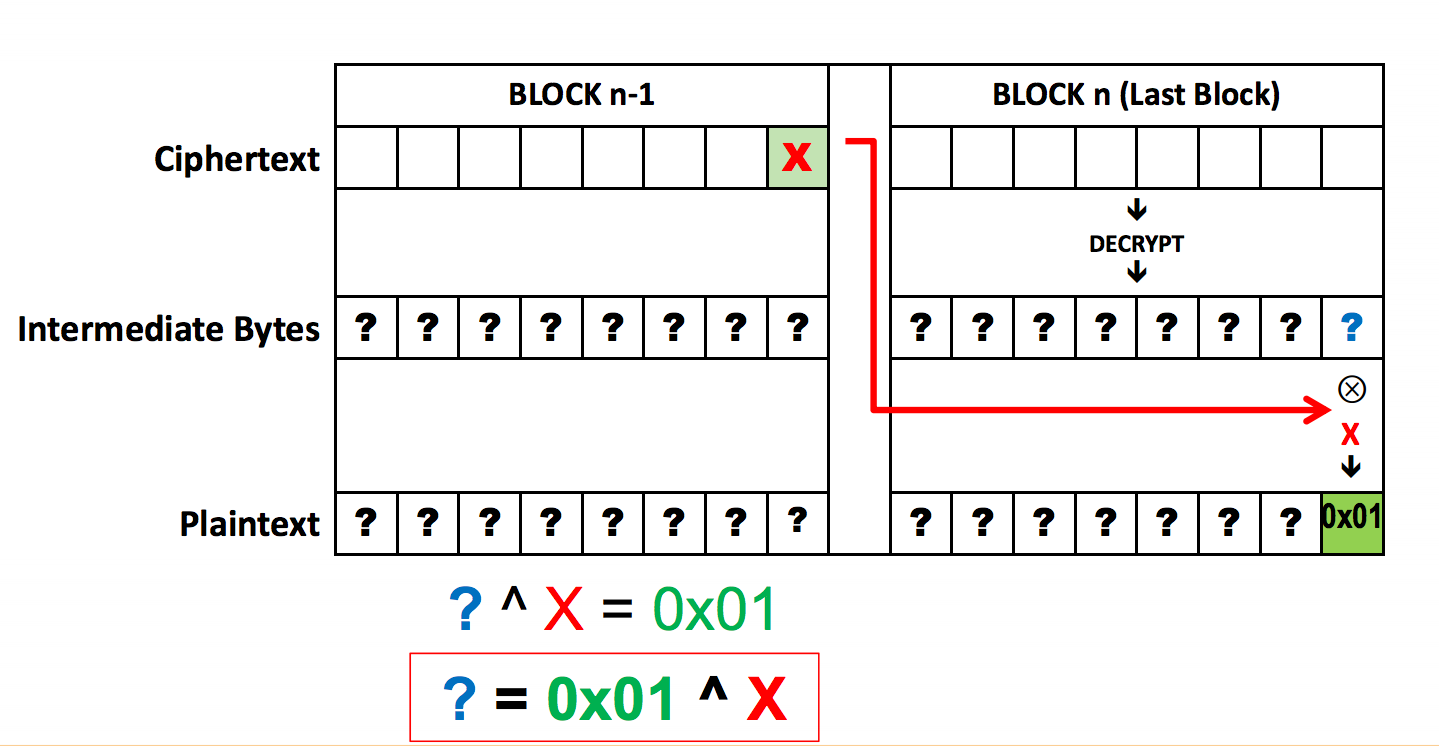

To begin, the attacker creates a Last Word Oracle. This first assumes

a 1-byte padding, so the format that the oracle would return as valid

is 0x01 XOR’ed with some particular value in the corresponding last

position in the n-1th block. Since the last byte, or word, can have

256 distinct values, the attacker can simply manipulate the n-1th

block, easily testing all values, until either the possibilities are

exhausted or the padding is returned as valid. If the possibilities

are exhausted, then the attacker instead tries 0x02, then 0x03,

and on until the padding returned is valid.

Source: Brian Holyfield, Gotham Digital Science

Once the attacker has learned the padding, a Block Decryption Oracle is constructed, using the values of the encrypted n-1th block to, byte by byte, guess the preceding byte, using the oracle’s pass/fail responses to confirm correct guesses. This method is then extended to decrypt all other blocks, as it is called on pairs containing a random block and a ciphertext block. (Again, the logical exception is the first block, assuming an independent initialization vector.) This is a terrifyingly efficient attack; to implement it, the attacker only needs (b * W * N)/2 trials, where b is the number of bytes per block, W is the number of possible bytes, and N is the number of blocks.

With the CBC Padding now added to the original ciphered message, attackers can alter this new message with blockwise operations in order to draw information out of the originally unreadable ciphertext. This information could potentially end up being authentication tokens, such as cookies, granting attackers personally identifiable information or the potential to hijack previous sessions.

BEAST: Plaintext Attacks Against SSL

Here Come The \(\oplus\) Ninjas by Thai Duong and Juliano Rizzo (2011)

In CBC block encryption, each plaintext block is XORed with the ciphertext of the previous block before being encrypted. An attempted guess at a plaintext block can be evaluated by encrypting the ciphertext prior to the block in question XORed with the ciphertext prior to the current block XORed with the guess; if the new ciphertext matches that of the block in question, then the guess is correct:

Guess G can be evaluated as equal to or unequal to plaintext Pj by setting Pi=G ⊕ Ci-1 ⊕ Cj-1 and checking whether or not Cj == Ci. An attacker would need to be able to view the encrypted messages and query the underlying CBC encryption system to be able to mount an attack based on this exploit.

Cryptographic systems are limited in their size and ability to store large plaintext messages, for this reason, most cryptographic systems encrypt messages block by block as they are sent. In the case where an attacker can append padding to a message before it is encrypted, an attacker can mount a blockwise chosen-boundary attack, in which the first byte of an unknown message is isolated by padding, enabling the attacker to guess at single bytes of a message rather than block-sized chunks.

The natural extension of this is to repeat the process such that once a byte of message has been guessed by the attacker, the padding is changed such that a single unknown byte of message is encrypted with padding and bytes known to the attacker, allowing them to continue guessing at single bytes of information.

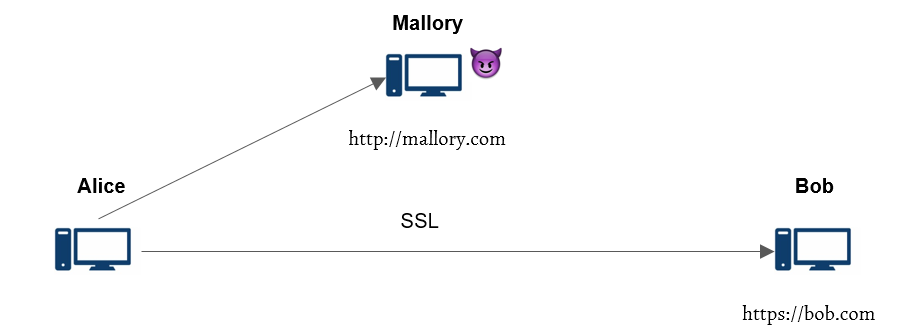

Duong and Rizzo go on to describe the process whereby this attack could be mounted on HTTPS to obtain a user’s HTTP cookie. The attack only requires that an attacker can view encrypted messages, can cause the client to make arbitrary encrypted requests, and that arbitrary plaintext can be added to out-going requests. In the described attack, the user is made to request a package with a padded end such that the first byte of unknown information in the request is isolated in an encryption with only public information. The attacker then makes guesses at that byte of information, appending plaintext to the request and watching the encrypted channel for a message block that matches the block containing the unknown byte of information. At that point, the guess that resulted in that message block is identified as the correct guess. The process is then repeated with a smaller padding until the user’s request header (including their HTTPS cookies) is revealed to the attacker.

Figure: Attacker (Mallory) is able to sniff encrypted traffic, force Alice to send cookie-bearing HTTP requests, and insert forged plaintexts in the conversation.

There are a few issues mentioned associated with this attack, but by using one of a variety of plugins, an attacker could make the user open bi-directional communication with the server. On this communication channel, the privileges required by the attacker to mount the attack would be easier to gain.

Lucky 13: Plaintext Recovery from Injected Ciphertext

Lucky Thirteen: Breaking the TLS and DTLS Record Protocols by Nadhem J. Alfardan and Kenneth G. Paterson (2013)

Similar in the vein of the BEAST attack using bitwise XOR operations to glean useful plaintext information, Lucky Thirteen offers yet another alternative means to get partial or even full plaintext recovery with just a simple man-in-the-middle injecting ciphertext into the original ciphertext. Based on analyzing how TLS and DTLS decrypt a given ciphertext, these attacks also rely on CBC-mode weaknesses.

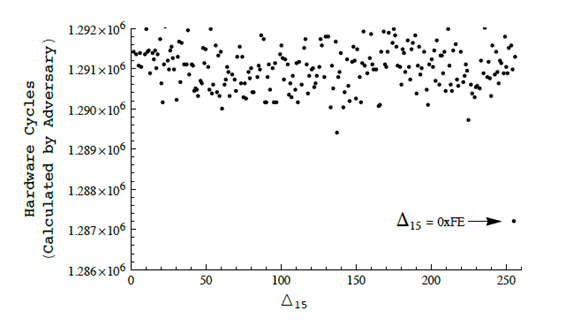

The Lucky 13 attack relies on a timing channel introduced by the difference in processing time between TLS records with correct and incorrect padding, requiring only a standard in-the-middle attacker for execution and providing recovered plaintext in the most severe case. This would indicate a major security flaw, even in comparison to the aforementioned BEAST attack. BEAST required capabilities beyond simple MITM on the part of the attacker. As a result, the authors of the paper disclosed their results to all major vendors to allow for patching before publishing.

The name “Lucky 13” is a reference to a specific breakpoint in the size of the padding on a given message. Both TLS and DTLS use the HMAC algorithm to compute MAC tags for messages. HMAC operates using a compression function on messages with lengths equal to multiples of 64 bytes, so TLS and DTLS pad out messages with remaining space.

After subtracting 8 bytes for the length field and 1 byte of mandatory padding, we are left with a maximum message length of 55 bytes that can be encoded within one block. This means that messages less than 55 bytes can be processed with only four compression function evaluations, and that in general the number of compressions is equal to

$$\left\lceil\frac{L-55}{64}\right\rceil+4$$

for messages of L bytes. The compression function is relatively expensive, so the difference between 4 and 5 iterations is distinguishable in good conditions. It is also possible to submit multiple requests as described below to amplify the differences if necessary.

The authors detail first a distinguishing attack, and then a variation allowing for full plaintext recovery. All attacks rely on the timing channel. Specifically, the authors describe in detail how it is possible to place a target ciphertext block at the end of an encrypted record, causing the decryption function to interpret the plaintext block corresponding to the ciphertext block as padding. Thus the amount of time required to process that block depends on plaintext bytes, leaking information.

Figure: Graph showing the differences in timing due to the number of compressions necessary for varying lengths of bytes.

Source: http://www.isg.rhul.ac.uk/tls/TLStiming.pdf

Conclusion

Through these readings and their respective explanations, we see that cryptographic protocols are often broken and need to be patched. There is always some threat model out there looking to exploit the first sign of weakness to decrypt and listen in on what should be a secure, encrypted channel. Through this last week, we focused on looking at padding oracle attacks which take advantage of the padding on the respective blocks in a CBC chain as they are passed from operation to operation. With the last word oracle and the BEAST attack, we saw how important this padding was to the security of the whole operation. With our look at Lucky 13, we were able to see that people were able to exploit the fact that one extra compression had to be done in certain situations to glean information about the message. As such, we see just from the padding, we have so many attacks.

There are so many aspects to SSL/TLS protocols that so many more exploits exist. So, what are ways that we can prevent these attacks? With the padding attacks, we saw that they tried standardizing error messages (but, why not just encrypt the message and send it back?). Should our strategy just be to move as quickly to the newest version of the security protocols? Should we add the MAC to the messages after encryption?

TLS 1.3 (the most recent release) has been drafted (and in the process of release) and has resolved many of these issues that have exploited weaknesses present in older versions of the protocol. However, its adoption rate has been very low and so it is important to bring this up as more and more operations should be moved over to TLS 1.3, as this seems to be the most secure system we have available right now and thus should be adopted.

Sources

https://tlseminar.github.io/docs/analysisssl3.pdf

http://www.iacr.org/cryptodb/archive/2002/EUROCRYPT/2850/2850.pdf

https://tlseminar.github.io/docs/beast.pdf

http://www.isg.rhul.ac.uk/tls/TLStiming.pdf