TLS Outside The Web

As the web evolves, taking on physical form with embedded devices, or becoming more abstracted with cloud computing, the question of how to secure these new kinds of connections becomes paramount. Can TLS work for non-web scenarios?

Sizzle and DTLS improve TLS performance in an attempt to make the protocol feasible on embedded devices with limited power and bandwidth - but sacrifice some security in the process. Developers of non-browser software like Cloud services, mobile apps, and payment transfer services misunderstand or intentionally disable vital security measures - and SSL APIs fail to communicate how to secure connections and implement authentication. Meanwhile, Amazon Web Services offers a heavily centralized alternative to securing the Cloud and IoT devices - but potentially at a high privacy cost.

Sizzle: TLS For Embedded Devices

Vipul Gupta, Matthew Millard, Stephen Fung, Yu Zhu, Nils Gura, Hans Eberle, Sheueling Chang Shantz. Sizzle: A Standards-based end-to-end Security Architecture for the Embedded Internet. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 2005.

Sizzle is an end-to-end security architecture for embedded devices that is fully implemented on the 8-bit Berkeley/Crossbow Mica2 “mote” platform. Capable of completing an abbreviated SSL (TLS 1.0) handshake in less than 4 seconds, this mote devices were envisioned to function as sensors/actuators connected to the wireless network. When this paper was published (2005), Sizzle on “mote” was the world’s smallest and least resource-intensive secure web server.

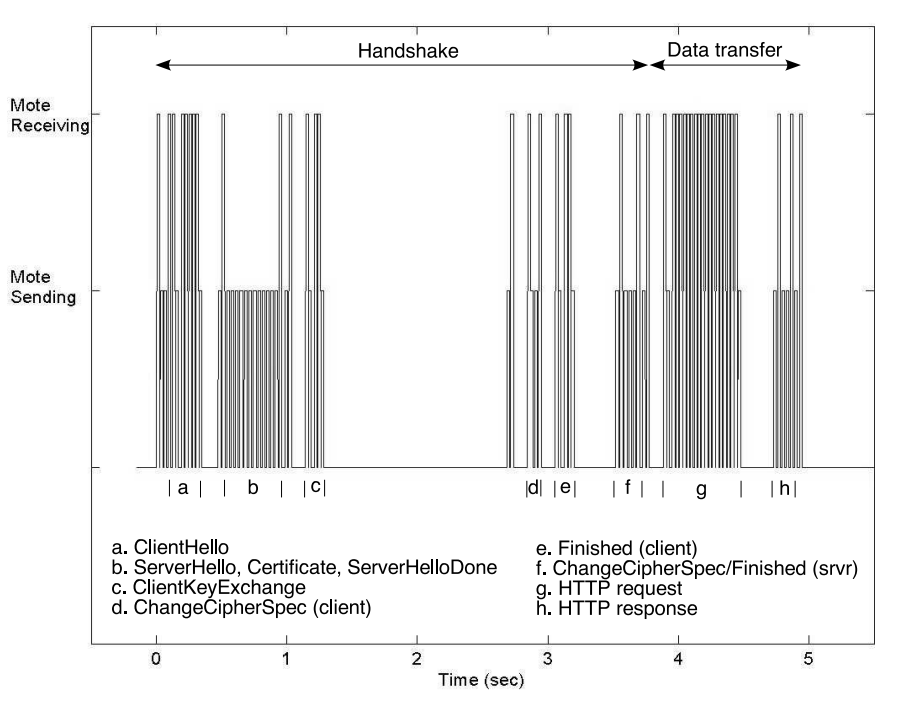

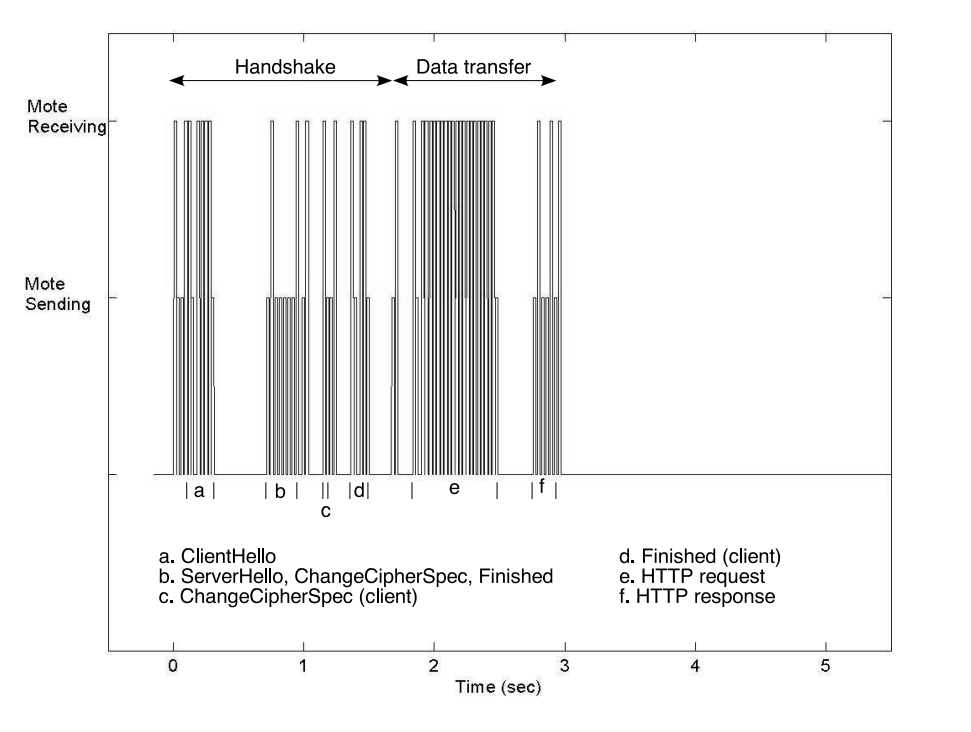

With the goal of allowing highly constrained embedded devices to offer secure connections, the authors of this paper uses 160-bit elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) to reduce computation for the system. When using ECC over RSA, there is a 4x speedup (or 5x speed up with session reuse) in computation speed of public/key cryptography. The figures 1 (full handshake) and 2 (abbreviated handshake) below show the comparison of the amount of time it took to transfer 450 bytes of data over HTTPS.

Authentication for the Internet of Things

Thomas Kothmayr, Corinna Schmitt, Wen Hu, Michael Brünig, Georg Carle. DTLS based security and two-way authentication for the Internet of Things. Ad Hoc Networks. May 2013.

Datagram TLS, also known as DTLS, is for all intents and purposes a “lightweight” version of TLS that can operate on devices that aren’t as powerful as traditional computers. Hence, it was a great addition for the internet of things devices as that revolution took off. According to its specification, it provides the same security guarantees as TLS except it is a stream-oriented service. It, however, does come with a downside. Namely, there is an overhead: tolerance for packet reordering and datagram loss. The former is pretty self explanatory, the latter is essentially stating that if the data is larger than the size of the datagram, it is possible that there be a data loss. Unlike, TLS, there are much fewer libraries that support this protocol, as can be seen in the graphic below:

So, we know of the following encryption techniques. When you have an access point and say a printer, that have a pre-shared key, we use WPA as a communication medium. Similarly, when we need secure connection between a sensor and a security end-point we use VPN, but what about a secure connection using TLS among the internet of things. That is the primary problem that DTLS seeks to solve. Since TCP and TLS incurs an overhead small, battery-starved, low-bandwidth devices, we choose to look at DTLS which uses a less strenuous UDP protocol and a lighter version of TLS, but still maintains the security guarantees.

Earlier, we discussed Sizzle, but it was important to notice that sizzle only provides one-way authentication between the client and the node. That is say you have a thermostat, this would allow someone to change your thermostat, but wouldn’t allow them to read the information. This is not exactly the security that we want.

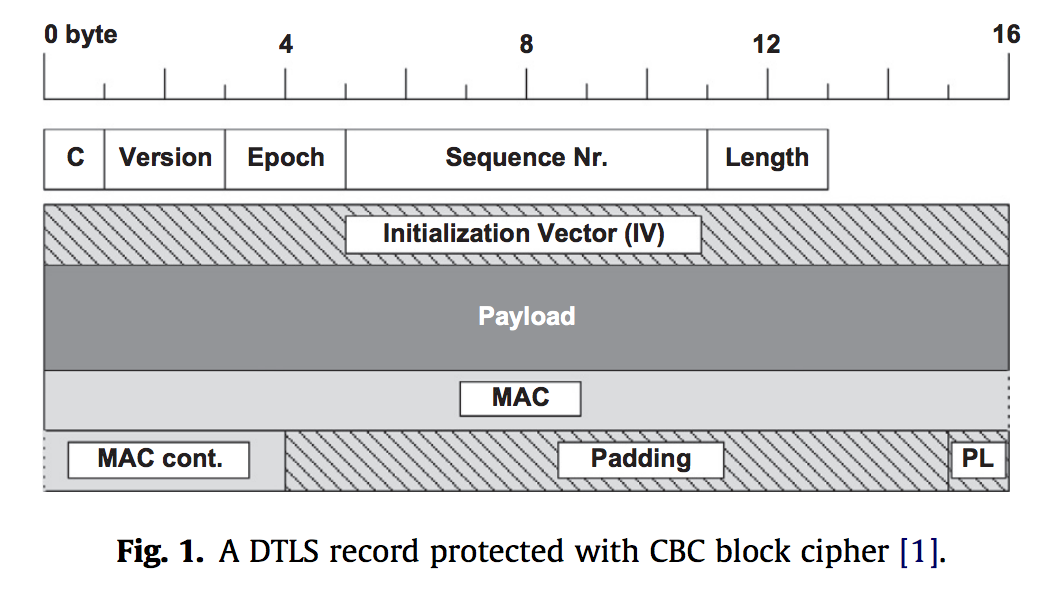

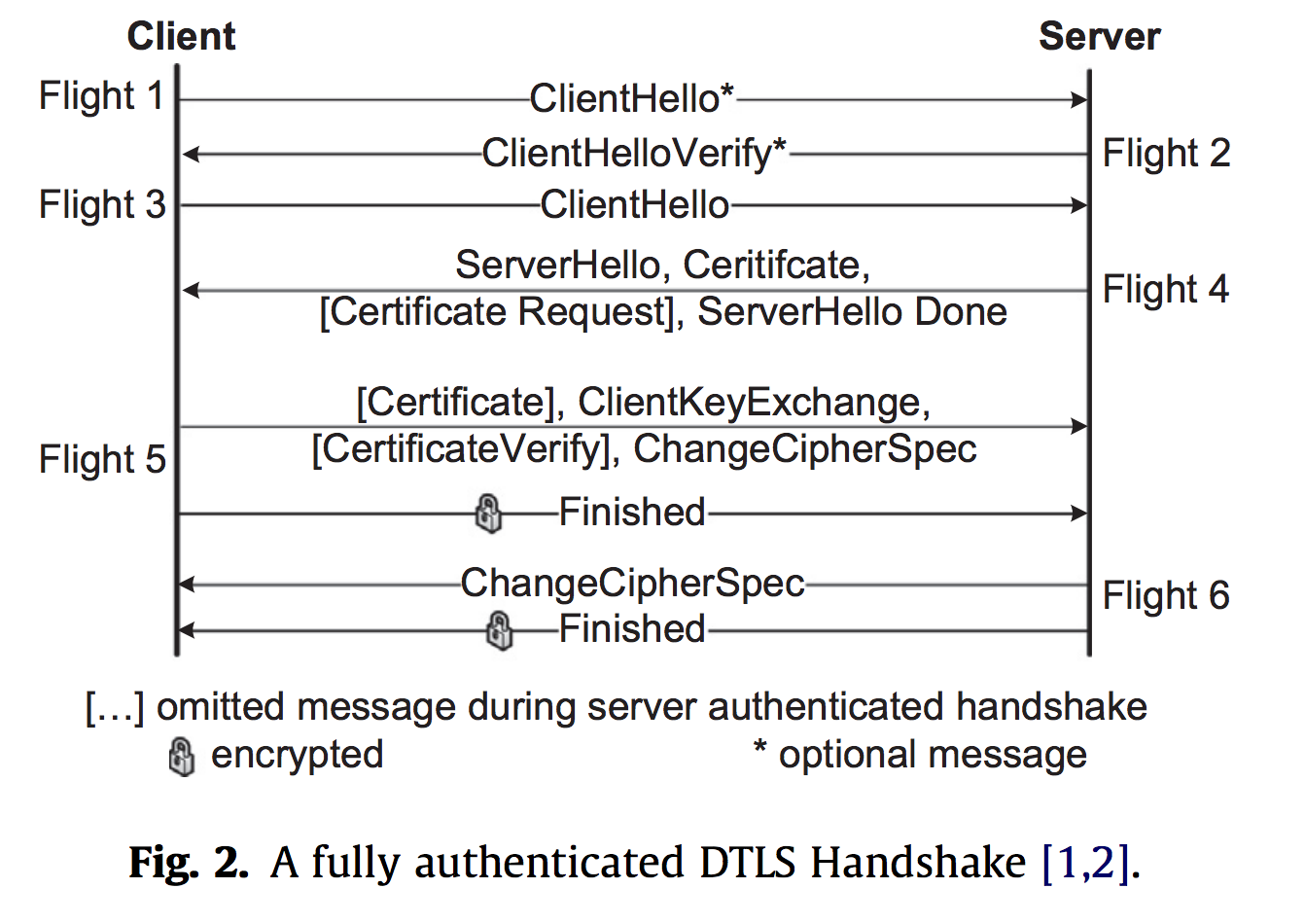

Let’s take a closer look at DTLS. The image below depicts a DTLS record. This looks similar to the record that we have seen with TLS and so there doesn’t seem to be too many causes for concern or intrigue about this structure. To its right, we have the handshake protocol. The main thing to notice here is that we have an extra, optional ClientHello and ClientHelloVerify before the rest of the protocol, which matches with what we’ve seen all semseter with TLS.

This security protocol is an application-layer security protocol. The reasons for using this are that lower-layer security protocols do not provide end-to-end encryption and the secure connections must be established to form a mesh network. This is better than routing algorithms that are agnostic of the payload protection, which means that you may have data sent over a non-secured connection or node.

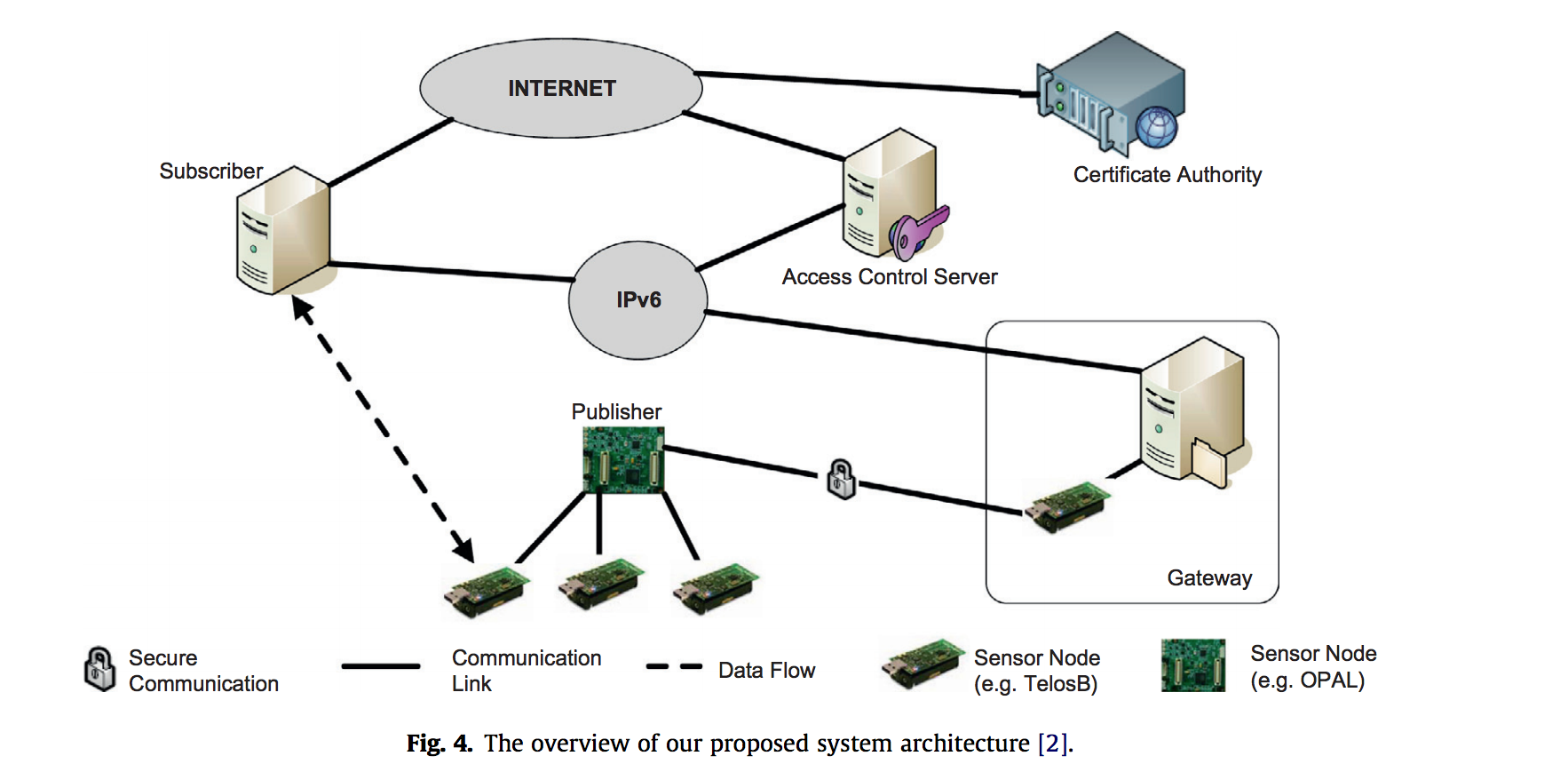

Finally, we can see how the proposed system actually works. This system uses a system of publishers and subscribers. Each of these can be considered the entities in the secured network. There is an access control server which stores teh access rights for all teh publishers (or motes). To intiialize any connection, the subscriber is verified by access control and is granted a ticket. The subscriber then presents this ticket to the publisher and the publisher verifies its legitimacy setting up the connection. In the larger scheme of things, the connection may look like:

Source: DTLS based security and two-way authentication for the Internet of Things

So overall, when looking at the internet of things, we need to be wary of achieving performance, energy consumption, memory and other limiting factors that the hardware has in order to achieve some level of security. Through DTLS, the researchers presented they were able to create a system that was fairly secure and was able to experience speedups of up to 163 milliseconds based on the protocol and encryption being used. Overall, we are able to see that creating a secure network for the internet of things is slowly manifesting into a reality.

The Most Dangerous Code In The World

Martin Georgiev, Subodh Iyengar, Suman Jana, Rishita Anubhai, Dan Boneh, Vitaly Shmatikov. The Most Dangerous Code in the World: Validating SSL Certificates in Non-Browser Software. ACM CCS 2012.

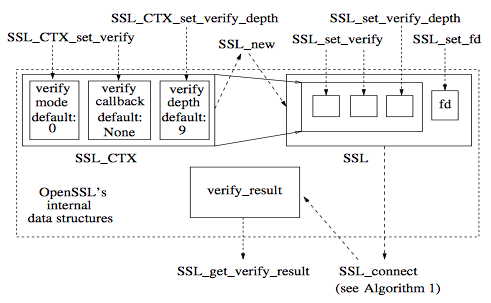

SSL verification for non-browser applications is nearly always compromised. These applications don’t implement SSL directly, but rather use libraries or wrappers which can have various flaws and vulnerabilities. These added vulnerabilities exist for a variety of reasons, but many of them are introduced because of a lack of security understanding in app developers and poor APIs. Rather than high-level security properties of network tunnels, many APIs divulge low-level details of SSL protocol to app developers. In many cases, options values associated with API functions are misinterpreted by app developers, leading to security risks. In other cases, attempts to fix certificate validation bugs can lead to further insecurity, potentially leading the app developer to accidentally break or disable the certificate validation entirely.

While most apps should do chain-of-trust and hostname verification, few do either. Chain-of-trust is often bypassed altogether, and hostname verification is often done via Common Name instead of SubjectAltName as is recommended by RFC 2818. Many applications also do not have a robust system for checking certificate revocation or allowing the user to do so. OpenSSL provides chain-of-trust verification, but requires that applications do their own hostname verification, while JSSE may or may not do either. This dependency on app developers to understand and implement potentially complex verification is unreasonable and leads to security vulnerabilities.

To avoid shop-for-free attacks, many vendor websites use SSL tunnels to communicate sensitive payment information, and these tunnels are often not set up securely. Attacks were attempted in a controlled environment on these tunnels using self-signed certificates and incorrect Common Name certificates. In Amazon’s flexible payment service, false was sent to cURL in a parameter instead of 2. In a bug fix, this parameter was changed to true, which also bypasses Common Name checks and causes vulnerability to MitM attacks.

One issue for app developers is needing to test their applications before making them live, and for those tests they either need to get valid localHost certificates (which aren’t given out) or they have to disable their certificate validation. Developers often do not enable the validation afterward and “disabling proper certificate validation appears to be the developers’ preferred solution to any problem with SSL libraries.”

App developers should attempt testing using abnormal and invalid certificates. They should also protect themselves by not relying on libraries and not disabling certificate validation during testing. SSL library developers should also attempt to be more explicit about their functionality and should avoid giving responsibility for validation to app developers.

AWS IoT Security Overview

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the largest cloud service provider in the world, offering a wide range of products from computing and network resources to game development services. One of their newer offerings, AWS IoT, enables developers to link internet-connected devices to the cloud.

The use case for this service is the Internet of Things. Physical sensors in our homes, offices, and cities collect data from their surroundings. Software can then analyze this data and leverage actuators to effect changes in the environment. For example, smart thermostats use temperature sensors to decide whether to heat or cool our houses. These thermostats can learn our daily routines, allowing them to control the temperature more efficiently than classical programmable thermostats. Furthermore, since the thermostats are connected to the internet, homeowners are able to remotely control their home temperature from their mobile phone.

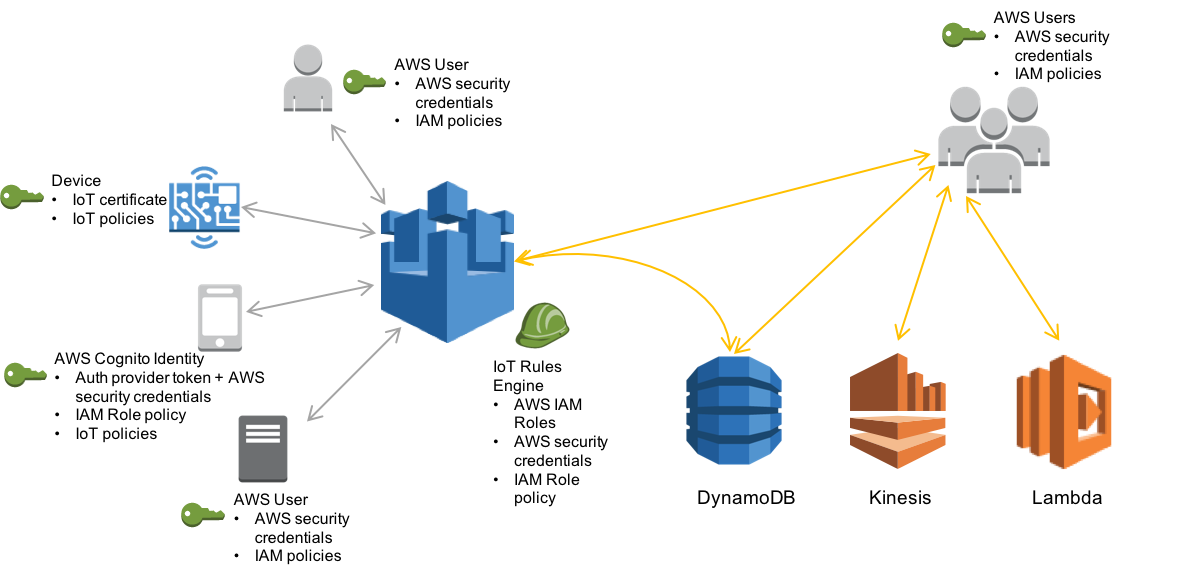

AWS IoT provides application developers a protocol, Message Queue Telemetry Transport (MQTT), for communication between Internet-connected things and the cloud. Sensors use MQTT to publish data to a message broker, which passes on the sensor readings to subscribing smart appliances and other devices. These messages are also processed by a rules engine, allowing developers to interface with other AWS services, such as their storage and data processing solutions.

Source: Amazon

All these messages to and from AWS IoT need to be secured. To ensure privacy, TLS is used to encrypt all MQTT traffic between devices and the message broker. Devices are authenticated using one of three identity types. First, clients can use the standard X.509 certificates used in HTTPS, which are authenticated using challenge-response TLS Client Authentication. AWS IoT also allows clients to use two AWS-specific identity types: IAM roles, and Amazon Cognito Federated Identities.

Even after a device has authenticated itself to the message broker, it is only allowed to execute an operation if it has been given the appropriate permission. An entity’s permissions are specified by AWS IoT policies, which are attached to the entity’s identity (certificate, IAM role, or Cognito identity). If an entity needs access to AWS services outside of IoT, IAM policies are used instead of IoT policies. These policies provide developers fine-grained control of authorization.

AWS End-To-End Hardware Security

Brandom Lewis. AWS, Microchip deliver trust anchor for end-to-end IoT security. Embedded Computing Design, 7 October, 2016.

Digital certificates are ingrained in almost every aspect of our digital lives. Signed by Certificate authorities (CAs), they help authenticate the identity of parties involved in the electronic exchange of information, preventing potential threats such as MITM attacks. With the Internet of Things (IoT) introducing billions of clients that communicate with the cloud in a two-way fashion, the requirement for mutual authentication of both clients and servers has steadily increased nowadays.

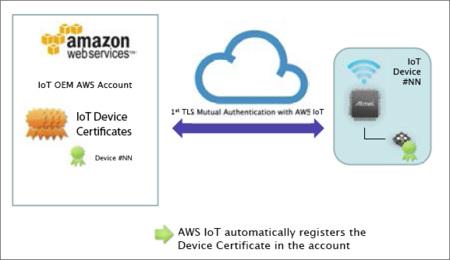

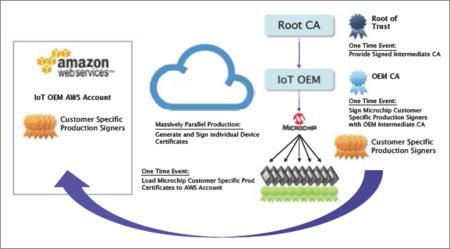

To solve the problems related to certificate provisioning for client-side devices, Amazon Web Services (AWS) released “Use Your Own Certificate” feature this April. It allows original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to register digital certificates signed by a third-party CA with the AWS IoT platform using an API, which, could happen even before the devices come online. This provides a new possibility for OEMs to generate cryptographic keys for device during its production period. The latest capability in the AWS IoT portfolio, Just-In-Time Registration (JITR), is also partly based on such process. As the term implies, devices can automatically connect to and be recognized by the AWS IoT cloud the first time they request service from the platform. By ensuring them being pre-equipped with unique, trusted private keys and correct server configurations and policies, such immediate, autonomous onboarding of devices with cloud services can maintain secure despite the large numbers of connections.

Fortunately, good news have arrived from hardware side of IoT spectrum as well. One example is ECC508A, a 2 mm x 3 mm tamper-resistant CryptoAuthentication device based on elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) algorithms. The architectural features of the chip include internally encrypted memory, isolated power rails, a memory and logic shield, internal clock generation, and a lack of probe points to protect against different kinds of real-world threats. It also improves overall system performance when TLS transaction runs on hardware-based crypto accelerator. With the ECC508A acting as the root of trust, Microchip can act as a third-party CA, signing device certificates in an offline verification process. Then OEMs are able to access robust security and automatic cloud authentication by adding a single component to their bill of materials (BoM).

Security is still essential to the continued rollout of IoT in every market. Device makers now can separate security from business functions and continue to work upon that. The ECC508A evaluation kit has been available on the market, which must excite those who deeply concern and care about the future of cyber security.

Conclusion

As we have seen, TLS is being widely used outside of the web in embedded devices, the Internet of Things, Amazon Web Services, and many others. The problem, however, is how these devices choose to implement their own versions of TLS and the problems that ensue. We have seen interesting applications of TLS that seem to also fundamentally break the intended security inherent in the protocol. Many of the problems are actually just based on laziness in the production of these devices, such as pinning a single certificate to every type of a device.

Besides TLS, alternative protocols have been designed for minimal data use and enhanced security throughout all communication between these devices. Because of the limited resources provided by embedded devices and IoT devices, many of the protocols must consider how much CPU, battery, and memory will be used at a time.

As time goes on, more and more of these embedded devices will be in our homes and cities, and there is the very real possibility of our own physical safety being in harm’s way due to a compromised device. Internet enabled doors, heating systems, windows, safes, and more could hold the potential of being locked, overused, and unlocked to cause danger to their owner. While TLS never was designed with the idea outside of web use, we must begin to consider alternative protocols or improve current ones to ensure the security of our technology outside of our browsers.