The Future of TLS

HTTPS Traffic Analysis

Brad Miller, Ling Huang, A. D. Joseph, and J. D. Tygar. I Know Why You Went to the Clinic: Risks and Realization of HTTPS Traffic Analysis, Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium, 2014.

Recent research has begun to cast doubt on the confidentiality provided by HTTPS. Researchers from UC Berkeley found that it is possible to determine medical conditions, financial and legal affairs, and sexual orientation of visitors to popular HTTPS-secured websites.

To perform the attack on confidentiality, the researchers employed clustering techniques to reveal traffic patterns and then applied a Gaussian distribution to glean similarities between the targets’ browsing pattern and the researchers’ own traffic patterns. As part of the attack, the researchers needed to visit the same websites as the targets and provide combinations of inputs until their traffic patterns matched those of the targets, within a statistical range of error. They note that ISPs and large government organizations could feasibly gain access to such traffic patterns despite the low probability of another Internet user doing so.

Through detailed traffic analysis, third parties could theoretically fingerprint Internet users and extract valuable personal information from HTTPS-secured communications by exploiting a side channel—in this case, as in many others, timing information.

What’s more, this example is by far the only side-channel leak regarding HTTPS traffic—at least four other prominent works (the latest of which was published just this year!) examine multiple usage scenarios ranging from Netflix viewing history to search queries to Google Map requests:

- Andrew Reed, Michael Kranch. Identifying HTTPS-Protected Netflix Videos in Real-Time. CODASPY 2017.

- Shuo Chen, Rui Wang, XiaoFeng Wang, Kehuan Zhang. Side-Channel Leaks in Web Applications: a Reality Today, a Challenge Tomorrow. 31st IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (“Oakland”) 2010.

- IOActive Blog. I can still see your actions on Google Maps over SSL. February 2012.

More Traffic Analysis

TLS traffic analysis can be applied in many scenarios, including:

- Distinguishing between clients on the fly

- Forensics

- Intrusion detection

- Malware detection

- Homogeneous platform verification

- Honeypots

Techniques such as deep packet inspection and TLS flow fingerprinting can be used to distinguish clients, identify whether the encrypted connection is attributed to a Malware or not, and also be used for forensics, intrusion detection and homogeneous platform verification.

TLS fingerprinting

Brotherston, L. (2015). Stealthier attacks and smarter defending with TLS fingerprinting.

During an TLS handshake, most clients initiate a TLS handshake request in a unique way. TLS fingerprinting is usually used to recognize a particular client. In TLS fingerprinting, some elements of the Client Hello Packet are filtered and collected to build a database of signatures. The collected elements are usually the combination of TLS version, record TLS version, ciphersuites, compression options, list of extensions, elliptic curves and signature algorithms. The use of this combined elements is not only reliable in terms of remaining static for any particular client, but offers greater granularity than assessing ciphersuites alone, which has a substantially larger quantity of fingerprint collisions.

IPSec in IPv6: light at the end of the (VPN) tunnel?

IPv6 is the latest version of the Internet Protocol (IP), and the future of the Internet’s identification and location systems; it is slowly overtaking its widely used predecessor, IPv4, and promises to add significant security improvements in the form of the IP Security specification (IPSec). IPSec is a suite which authenticates and encrypts packets of data through a VPN tunnel over a network connection; a version of IPSec has been adapted for IPv4, though the issues we consider concern IPSec’s vulnerabilities in IPv6.

IPSec gateways

A vulnerability in IPSec gateways were recently uncovered as the “Packet Too Big”-“Packet Too Small” ICMP attack in GLOBECOM 2014. As described in the paper, an attacker with eavesdropping and injection access to IPSec encrypted packets can force an IPSec gateway to drop to its minimum possible transmission specification (Path Maximum Transition Unit) and cause major performance penalties and denial of service to the host. The root cause of the attack is in the impossibility of IPSec to distinguish legitimate ICMP packets from illegitimate packets, as well as several contradictions the Path MTU is managed by end hosts when the MTU is below the minimum packet size.

VPN vulnerabilities in IPSec

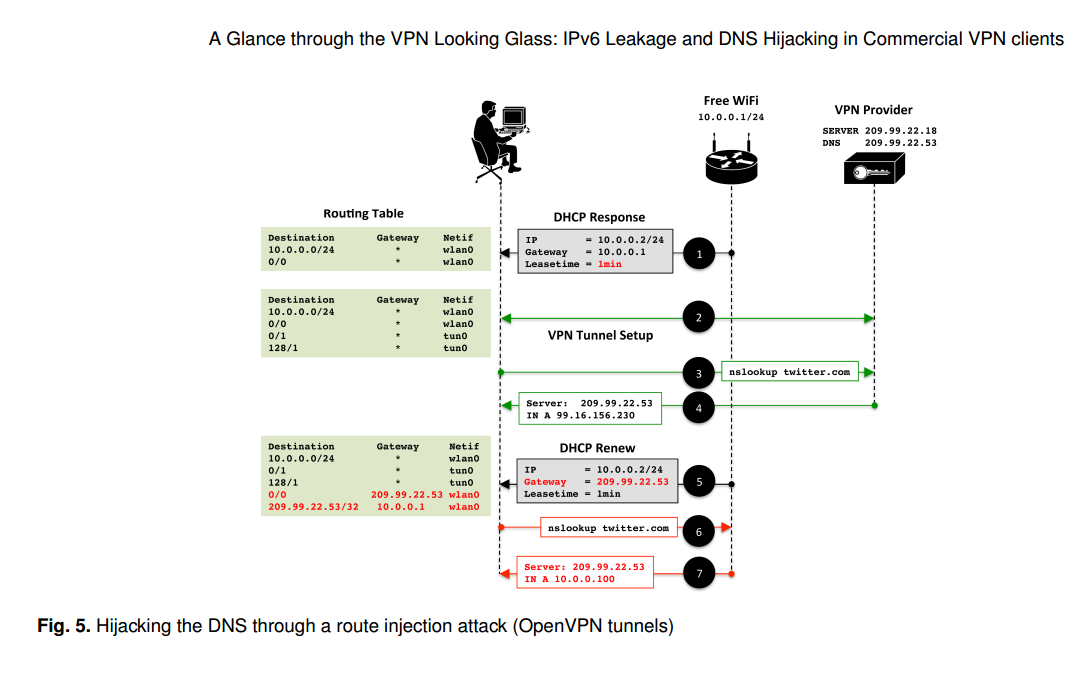

Vasile C. Perta, Marco V. Barbera, Gareth Tyson, Hamed Haddadi, and Alessandro Mei. A Glance through the VPN Looking Glass: IPv6 Leakage and DNS Hijacking in Commercial VPN clients. Privacy Enhancing Technologies 2015.

A paper in PETS 2015 uncovered several vulnerabilities in IPv6 traffic, including leakage and DNS hijacking. The vulnerability relies on the nature of IPv4/6 dual stack implementations on common operating systems.

Source: Perta et al., PETS 2015.

All VPN services surveyed rely on the correct configuration of the operating system’s routing table. Worryingly, no attempt is made to secure this operation. The simplest scenario is where the VPN client does not change the victim’s default DNS configuration (e.g., HideMyAss over OpenVPN). In this case, subverting DNS queries is trivial. The access point can simply use DHCP to set the victim’s DNS server to one that it manages itself. The adversary will then receive all DNS queries generated by the host.

The paper notes that “The simplest countermeasure to IPv6 leakage is disabling IPv6 traffic on the host.” Perhaps more sensibly, VPN clients could alter the IPv6 routing table to capture all traffic and prevent leakage from occurring.

QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections)

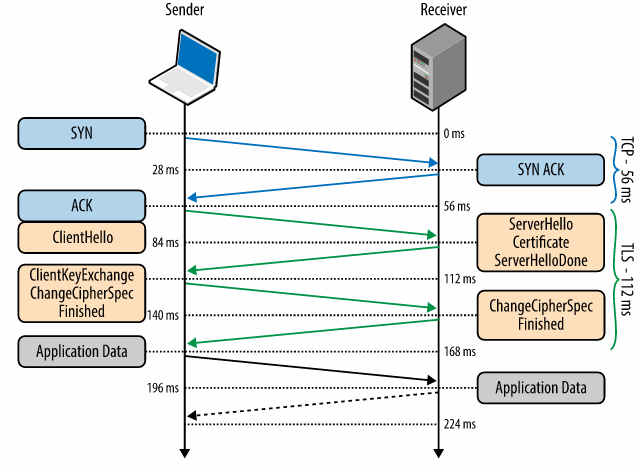

Internet today relies on TCP as a backbone for secure connections over the web. But TCP protocol introduces latency due to synchronization for channel setup, even before TLS handshake. The figure below shows that an average TCP connection takes 56 ms before the TLS handshake begins. This type of latency is not acceptable in mobile devices or in an area with poor internet reception.

TLS Handshake Time (Source: https://hpbn.co/transport-layer-security-tls/)

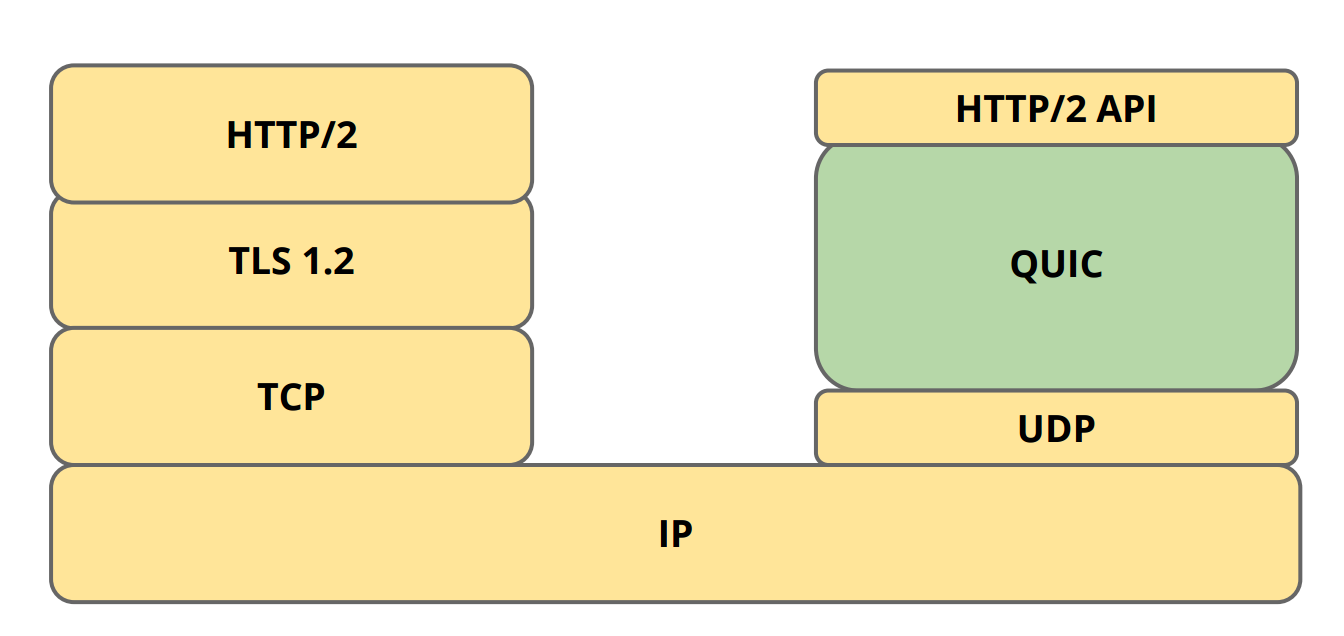

This motivates the need for faster secure networking by reducing the number of round trips required to establish secure connection. QUIC aims to achieve this by using UDP as backbone instead of TCP.

Implementing QUIC

QUIC was introduced by Google and it relies on UDP for fast secure connection. UDP provides quick connection and can handle out of sequence packets but requires resending of failed packets to prevent packet loss. It is an excellent alternative for faster secure connection if security is taken care by the application and leaving UDP to take care of the packet transmission and recovery. This requires both server and client side change in application logic to ensure security. Google has already implemented its crypto-layer and provides experimental libraries like libquic and goquic, but currently this can only be tested on Google servers.

QUIC Protocol Stack (Source: https://ma.ttias.be/googles-quic-protocol-moving-web-tcp-udp/)

InterPlanetary File System (IPFS)

Looking forward to the future of web, it is possible that new models of the Internet will come into play. One such candidate model that is being developed today is the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). The goal of IPFS replace the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and treat the web as though it is a filesystem and to make the web distributed. Let’s unpack what this means and what IPFS can potentially do for the web.

The Web, Distributed

A key distinction to make between models of the web are the way “nodes,” or computers are linked together. On one end of the spectrum there is the centralized model where a single server contains all the content on the web and every computer must connect to it to retrieve a particular page. If this sounds dystopian and inefficient, it is. This single server would essentially have full say over what content gets to appear on the web and who gets access to it. Thankfully, that is not the model of the web we live under.

On Distributed Communications - Baran

Our web is better described as a decentralized network. There is no central authority in charge of all of the data on the web. Rather, there are millions of servers that host web pages that anyone can access (most of the time). Anyone can create a server and host whatever they want. As the web has evolved however, we see that this model is perhaps not as ideal as we might like; most of the servers that make up the web are controlled by a few server-providers such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft. The servers of large corporations such as Facebook tend to function as content repositories for billions of people instead of each person controlling his or her identity on the web. As such, the network can be described with a long tail distribution:

Long Tail Distribution

A few servers have the most traffic and the traffic of the remaining servers exponentially decreases and trails off to nil.

What IPFS proposes to do is to create a distributed internet, where the actual distribution of content is done on a peer-to-peer basis. All of the nodes in the network host a nearly-equal amount of content. So why is this good? In both the centralized and decentralized case, a computer must download a file from a single server and deal with that servers busyness. With a distributed network, the computer can instead download content simultaneously from many of its peers. With video delivery for example, the P2P approach could save up to 60% in bandwidth costs.

The Web, Preserved

The second idea that makes IPFS different is that it has historic versioning built in. If you’re familiar with git and the way each file has a history associated with it, then this concept should be right at home for you. If not, then imagine it this way: say you run a blog and one day you decide to add a new post to it. Both the way your blog was without the new post and the way it is now with the new post are saved within the network. So why is this a good thing? Take the case of Yahoo GeoCities. Back in the early 2000s Yahoo provided GeoCities as a place where people could set up small websites and publish content to them. However in 2009 Yahoo decided that GeoCities was no longer a profitable business for it and shut it down. At the time there where about 38 million user-built pages on GeoCities. Any content that was not preserved by the Internet Archive was lost.

How It Works

When someone adds a file to the IPFS network, all of the blocks within the file are hashed. IPFS deduplicates files on entry so if any of the blocks are duplicates of some other block (as shown by comparing the hashes of the blocks), the duplicate block will not be re-added to the network. As mentioned, version history is tracked for every file so the blocks are given a version number (v1 in this example). The file is then distributed across the network to nodes that are “interested in it.” This means that only nodes set to store a particular topic will store the file and its blocks. Indexing information is also stored with each node so that the network as a whole is aware of which node is storing what information. If a lookup is done on the file then the network is queried for nodes storing the content corresponding to the unique hash associated with the file. If you are more interested in how IPFS works, I recommending taking a look at the IPFS whitepaper.

Will it Work?

Technically, yes. The IPFS network is an actual thing that one can join and use now but it remains to be seen whether IPFS can gain widespread adoption. Currently, one of the major problems the network faces is that it is slow both for storing and querying content. This is partially due to the small size of the network, but also because of the overhead that comes from all of the necessary information, like the hashing of the files and their blocks, needed to support the network’s functionality. Perhaps the largest problem is the deep entrenchment of the HTTP protocol. Nearly everything on the web uses HTTP for transporting content, and unless there is a clear and present need for a switch to a different architecture, IPFS may remain wishful thinking for a long while.

Multi-Context TLS

David Naylor, Kyle Schomp, Matteo Varvello, Ilias Leontiadis, Jeremy Blackburn, Diego Lopez, Konstantina Papagiannaki, Pablo Rodriguez Rodriguez, and Peter Steenkiste. Multi-Context TLS (mcTLS): Enabling Secure In-Network Functionality in TLS. SIGCOMM 2015.

Normal TLS facilitates connections between only 2 communicating parties. However, in the wild, most connections pass through various middleboxes along the way that provide additional functionality, such as intrusion detection and parental controls. Current TLS connections with middleboxes require the middlebox to generate fake certificates for the intended site. The network administrator sets up each machine on the network with a custom root CA for the fake cert. The middlebox then connects to the site, meaning that the client doesn’t know what happens in this part of the connection (ex: the middlebox could downgrade the connection).

In order for TLS to support middleboxes, it must incorporate two principles: least privilege and endpoint agreement.

Least Privilege

Multi-Context TLS (mcTLS) implements least privilege by defining 3 types of connection users: readers, writers, and endpoints. In this setup, the endpoints are the client and the target server, while readers and writers are middleboxes. Readers have the least privilege (read-only), writers have additional wite privileges, and endpoints have full access to the network traffic. In mcTLS, readers encrypt the data and generate a MAC for the ciphertext. This MAC verifies that no 3rd-parties modified the data. Writers then create a second MAC for the reader traffic (ciphertext + reader_MAC), which confirms that the readers did not modify the data (since readers do not have write access). Finally, the endpoint also creates a MAC on the entire stream to act as a signal of whether any writers modified the data (although they do have permission). Readers and writers only receive the keys that they need to perform their operations, whereas enpoints receive all keys.

- MAC

- Readers encrypt data, create MAC

- Writers create MAC - verifies no 3rd parties modified data

- Endpoints create MAC - signal of whether writers modified data (they are allowed to)

- Readers, writers only get keys they need - endpoints get all keys

Endpoint Agreement

mcTLS key distribution implements the principle of endpoint agreement. Each middlebox (reader or writer) only receives a subset of the connection keys determined by its functionality. Permissions, which are substantiated through the keys, must be explicitly granted to a middlebox by both the client and server. Each side (client and server) provides each middlebox with half of each key granted by that side’s policy. The middlebox can only use keys (permissions) granted by both the client and server. Thus, the mcTLS Handshake Protocol includes key distribution for the middleboxes in addition to the client and server.

Performance

mcTLS requires most keys to be distributed and therefore involves larger packets in the handshake. This packet size increases with the number of encryption contexts (permissions) and the number of middleboxes. However, the hanshake includes the same number of trips as the standard TLS handshake and therefore requires roughly the same amount of time.