TLS Interception and SSL Inspection

The fact that “SSL inspection” is a phrase that exists, should be a blazing red flag that what you think SSL is doing for you is fundamentally broken. Compounding the problem are the mistakes that SSL inspection software authors are making.

– Will Dormann (2015), Carnegie Melon Software Engineering Institute CERT/CC Blog

Recent History

TLS Interception, also referred to as SSL Inspection, is a topic that has been in the news in recent years and months. Back in 2014, researchers from Brigham Young University published a paper titled TLS Proxies: Friend or Foe? where they deployed a Flash application via Google Adwords campaign to identify client-server certificate mismatches across the web. They discovered a wide prevalence of adware, malware and TLS proxy products presenting certificates trusted by the client but not issued by the server – and in most instances acting in a negligent manner by introducing security vulnerabilities. One parental filter they tested replaced untrusted certificates with trusted ones, bypassing browser warning screens. This is exactly the type of passive attack HTTPS aims to prevent.

Vulnerabilities involving two advertising injectors, one of which was preinstalled on Lenovo PCs, were found to severely compromise the security of end users in February of 2015. Later that same year, German journalist Hanno Böck looked at three popular antivirus suites and found that all lowered security by either exposing end users to vulnerabilities like FREAK and CRIME or supporting less secure encrpytion algorithms.

In early 2017 researchers teamed up with Google, Mozilla, and Cloudflare for an internet-wide survey - The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception ( Zakir Durumeric, Zane Ma, Drew Springall, Richard Barnes, Nick Sullivan, Elie Bursztein, Michael Bailey, J. Alex Halderman, Vern Paxson; in NDSS 2017). TLS interception software was assessed based on how the TLS connection observed from the client differed from the TLS parameters advertised by the client. In all but two of the tested products, security was reduced, and in some cases serious vulnerabilities were introduced. Most recently in February of 2017, a Chrome 56 update took down almost a third of Montgomery County Public School’s 50,000 fleet of Chromebooks offline, because the school systems web filter, BlueCoat Proxy, did not properly handle TLS 1.3. When Chrome attempted to connect via TLS 1.3, the Bluecoat software abruptly terminated the connection, rather than negotiating for TLS 1.2.

How SSL/TLS interception works

SSL/TLS interception is performed by software on “middleboxes” located in between the client and HTTPS website or on the client’s machine, in the case of malware, anti-virus software, and ad injectors. Middlebox software has both legitimate and illegitimate use cases including proxies or content filters, antivirus suites, content cachers, advertising injectors, and malware.

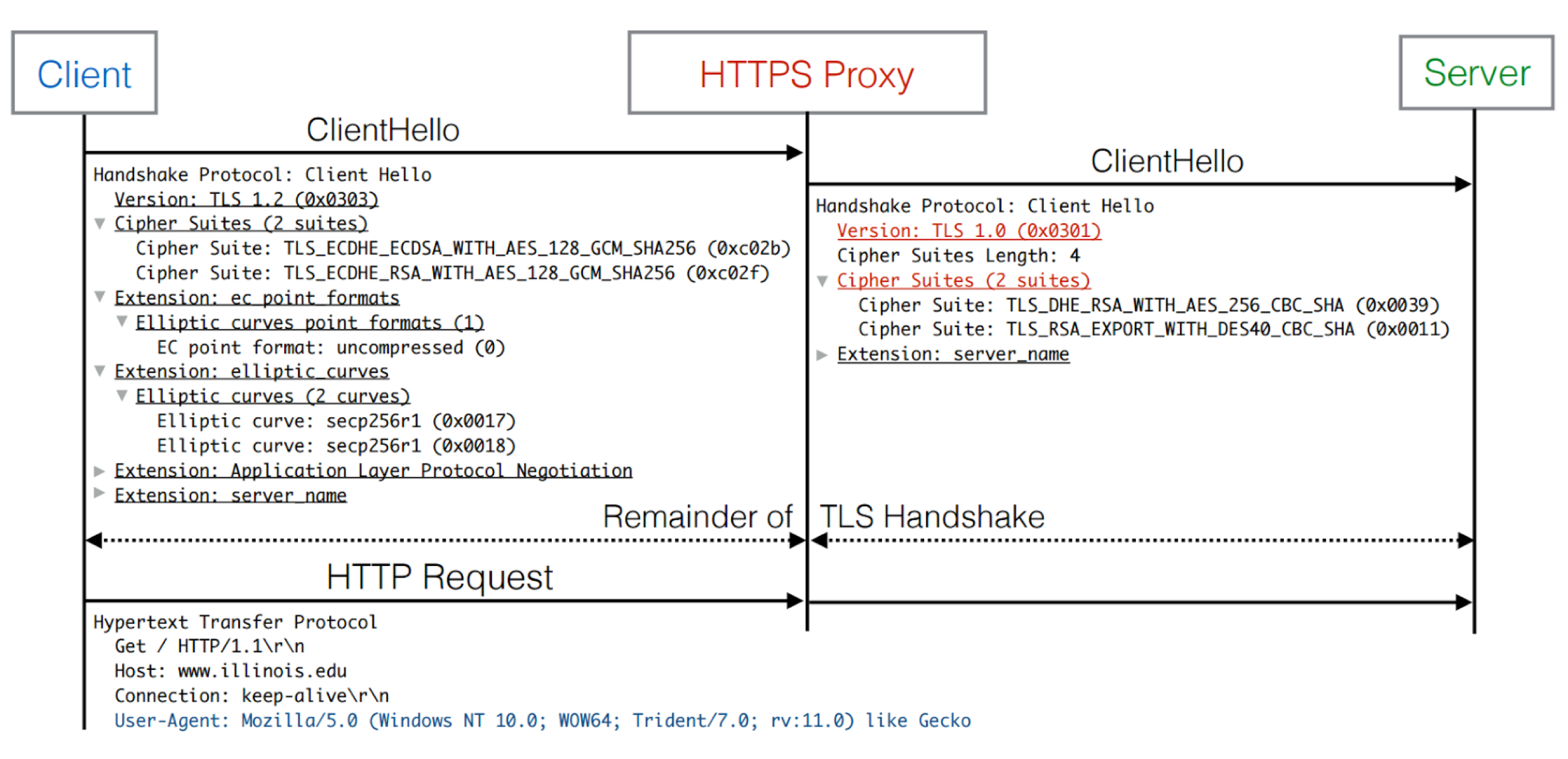

Source: The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception (2017)

Middlebox proxy software relies on the client having previously installed a root certificate onto their operating system. Any outgoing SSL/TLS connections from the client are terminated and re-established by the proxy to the server, which acts as an in-the-middle attacker. In an ideal deployment, the proxy’s ClientHello mirrors the TLS parameters expressed in client’s ClientHello, to provide the same expected parameters to the client. The proxy can then inspect plaintext and establish a TLS connection back to the client using the installed certificate to circumvent browser warnings and silently intercept the connection between client and server.

Superfish

In 2015, there was in an incident involving Lenovo PC’s shipped with a preinstalled image advertisement optimizer developed by Superfish. Superfish used Komodia’s tool “SSL hijacker” to intercept HTTPS connections in order to gather image data for its ad optimization engine. Komodia’s tool is similar to to all SSL inspectors — it first installs root certificates on the client machine and then MITMs all TLS connections to HTTPs websites, issuing the preinstalled Komodia certificate to the client instead of the target HTTPS server’s certificate to bypass browser warnings.

To enable it to generate trusted (by the browser based on the new root CA key installed) certificates for any website the user connects to, it needed to generate new certificated on-the-fly, so the private signing key for the root CA needed to be stored on the user’s device. This means that the private key for the certificate was visible in the software and could be trivially extracted by the end user. In addition, Komodia used the same private key for every machine running Superfish. It didn’t take long for security researcher Robert Grahm to crack the password for the private key (hint: it was ‘komodia’). With this key, an adversary could MITM any client running Superfish on their laptop by using using a copy of this hardcoded certificate. To compound this, users were not alerted to the presence of Superfish software on their new Lenovo laptops.

Komodia released a security notice saying they fixed the issue by updating the software to create unique certificates per installation and randomly generated passwords. They also addressed other potential vulnerabilities such as updating their list of supported cipher suites and verifying certificate revocation statuses (they support OCSP). The countermeasures outlined in their security notice serve as a starting point for all HTTPS interception software developers.

PrivDog

Shortly after the Superfish incident, another piece of TLS interception software named PrivDog made by Adtrustmedia was also found to be vulnerable. PrivDog is an advertising program which intercepts HTTPS connections and replaces “bad” advertisements with advertisements approved by Adtrustmedia.

Privdog, like the aforementioned Superfish, simply replaced certificates for a HTTPS server with new certificates signed by the root certificate they installed on the affected machine. However, the Privdog software performed no validation of the original certificate presented by the target server. Not only did it make untrusted certificates seem trusted, but legitimite websites with EV Certificates were replaced with PrivDog’s self signed certificate removing the green browser indication. Any website an affected user visited with an invalid certificate would appear valid, without browser warnings. An adversary could easily MITM a client running PrivDog by simply advertising a self-signed certificate!

The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception

The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception. Zakir Durumeric, Zane Ma, Drew Springall, Richard Barnes, Nick Sullivan, Elie Bursztein, Michael Bailey, J. Alex Halderman, Vern Paxson. Network and Distributed Systems Security Symposium (NDSS) 2017.

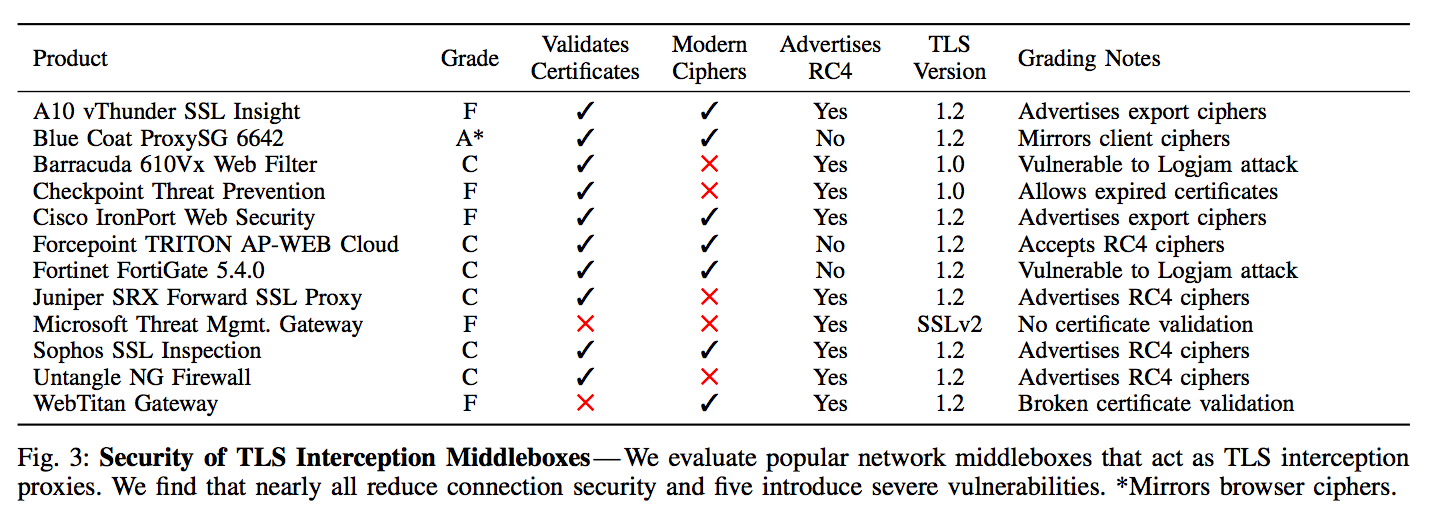

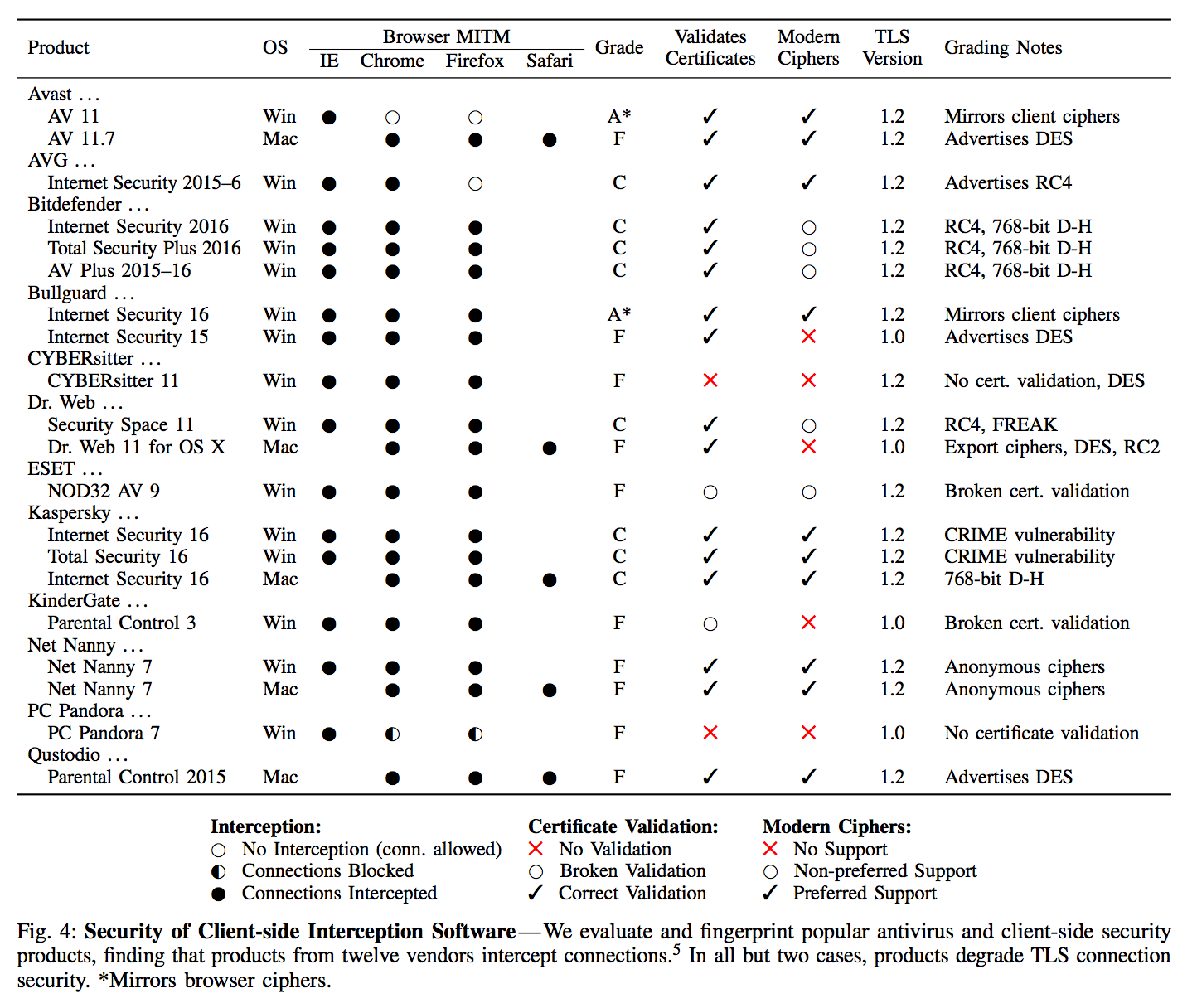

In early 2017, researchers teamed up with Google, Mozilla and Cloudflare in efforts to measure TLS interception in an internet wide study. They noted that TLS interception software can be detected from the server’s point of view by identifying a mismatch between popular browsers TLS handshakes and the observed handshake. Going one step further, by observing the TLS handshakes of popular interception software they were able to construct fingerprints for some of the most widely used interception products.

The study measured interception from the vantage point of the Cloudflare CDN, Firefox Update servers, and popular e-commerce sites. Important results from the study found that about 5-10% of measured HTTPS connections were intercepted, and much of the software reduced the security of the end user in one way or another, with 97%, 54%, and 32% of connections to Firefox, Cloudflare, and e-commerce sites becoming less secure respectively. Interestingly, the only middlebox software to earn a grade of ‘A’ was BlueCoat Proxy.

Source: The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception

Chrome 56 update breaks Bluecoat Proxy v6.5

Note these issues are always bugs in the middlebox products. TLS version negotiation is backwards compatible, so a correctly-implemented TLS-terminating proxy should not require changes to work in a TLS-1.3-capable ecosystem […] That these products broke is an indication of defects in their TLS implementations

– David Benjamin, Chromium Bug Tracker (2017)

On 21 February 2017, shortly after the above paper was published, mishandling of TLS 1.3 connections by BlueCoat Proxy left thousands of clients without internet connection after an automatic Chrome 56 update. The problem wasn’t that BlueCoat Proxy didn’t implement TLS 1.3, but that it didn’t gracefully renegotiate down to TLS 1.2 which it does support. Instead, the software simply terminated the incoming connection. This left tens of thousands of Chromebooks used by Montgomery County Public Schools students temporarily unable to connect to the internet. The temporary solution was for individual users to alter Chrome’s internal settings to disable TLS 1.3 chrome://flags/#ssl-version-max until a more general solution was delivered by the following day by Chromium, which rolled-back TLS 1.3 support by default.

Going Forward

Whether it be at the cost of availability or end user security, these incidents expose the fragility of TLS interception software. Google has reached out to middlebox vendors in efforts to help them resolve the issues, but system administrators should consider the risks of TLS interception seriously. There are, however, situations where it is necessary such as when companies are legally required to monitor traffic of their employees to comply with regulations (such as in the financial industry). Vendors should independently strive to fix their products for the security of their users at the same time. Organizations who deploy TLS interception software should choose products in an informed manner and carefully consider the risks imposed by interception software.

Source: The Security Impact of HTTPS Interception (2017)