Certificates

Introduction

So far, we have learned some real-world TLS attacks and how they bring potential vulnerabiliting in different situations. Since the core SSL/TLS technology has persisted as the basis for securing many aspects of today’s Internet for more than twenty years, including data transfer, user passwords, and site authentication, it is important to also consider issues beyond the protocol.

This week, we’ll go on to discuss practical issues with TLS including HTTPS, certificates, key management and an attack called SSLstripping.

Trust Issues and Enhancements

SoK: SSL and HTTPS: Revisiting past challenges and evaluating certificate trust model enhancements, Jeremy Clark and Paul C. van Oorschot, IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (“Oakland”), 2013.

Certificates

The TLS protocol enables a client and a server to establish and communicate over a secure channel. Assuming such a secure channel can be created, authenticating the server still remains a challenge. HTTPS attempts to solve this problem using certificates, which bind public keys to servers. Web browsers trust certificates that are issued by certificate authorities (CAs).

A certificate is bound to a server through its domain name. When requesting a certificate for a domain name from a CA, the requester is challenged to demonstrate control of the domain name. Upon successful validation, the CA will digitally sign a domain validated (DV) certificate for the entity.

Stronger verification techniques are available due to security issues with hostname validation. A common verification technique used by CAs is to send an email to an email address associated with the domain. This becomes an issue when an attacker is able to spoof DNS records, such as through a DNS cache poisoning attack. Issues may also arise when an attacker is able to register an email address at the domain. For example, an attacker was able to convince a CA that owned login.live.com by registering sslcertificates@live.com. In response, CAs offer extended validation (EV) certificates to entities willing to pay a premium and undergo more stringent validation.

Anchoring Trust

Although anyone can create a certificate for any site they want, clients should only trust a certificate if it has been signed by a CA they already trust. Browsers com pre-configured with a default list of CAs known as trust anchors. Mozilla’s Firefox 15 browser includes approximately 150 trust anchors.

Users may also add additional trust anchors to their system. This is commonly done by organizations in order to MITM their users HTTPS connections to perform content inspection, or by users who want to inspect the contents of their own HTTPS requests.

Because any trust anchor is able to issue trusted certificates for a website, an adversary need only target the weakest CA in order to obtain a fraudulent certificate. Furthermore, governments are in a position to compel CAs to create valid certificates to be used in MITM attacks.

To prevent misuse of fraudulent certificates, webservers may use HTTP Public Key Pinning (HPKP) to remember a presented certificate, and warn the user if a different certificate is ever presented for the same domain in the future. This way, even if an adversary has obtained a certificate that is trusted by a browser, they will be unable to perform a MITM attack. However, this technique requires a user to blindly trust the first certificate that the webserver pins. An effective alternative is for browser vendors to include a list of certificates to pin within the browser.

Transitivity of Trust

In addition to signing certificates for webservers, trust anchors can issue certificates allowing other organizations to also act as CAs. While Firefox includes nearly 150 trust anchors from approximately 50 organizations, hundreds of organizations, including the US Department of Homeland Security, are trusted intermediate CAs.

Client software does not generally maintain a list of intermediate CAs. Rather, they use a chain discovery mechanism to trace a server’s certificate back to a trust anchor. Such a chain must be carefully validated to check that each intermediate CA occurring in the chain has actually been granted authority to sign further certificates. This check was previously skipped by Microsoft’s CryptoAPI and Apple’s iOS.

One way to ensure that every intermediate CA is visible to users is to publish a list of every valid certificate. This way, clients are able to know about intermediate CAs before their certificate is encountered. This is important because intermediate CAs can have just as much power as the trust anchors.

Maintenance of Trust (Revocation)

Sometimes a certificate needs to be revoked, such as when a site is compromised or abandoned, the domain name is exchanged, or the CA becomes aware of mistaken issuance. This revocation status must be readily available through the CA, either through a certificate revocation list (CRL) or an online certificate status checking protocol (OCSP).

Because this revocation information may be unavailable, browsers choose to accept certificates when the information cannot be located. Thus an adversary who is able to prevent a browser from obtaining revocation information may be able to cause a revoked certificate to be accepted.

Besides the list of all valid certificates described above, one way to combat unreliable revocation is for webservers to provide timestamped OCSP status reports, a technique known as Certificate Status Stapling. Alternatively, if certificates were issued to be valid for a shorter time, the impact of missing a revocation is lessened. Currently, certificates are often valid for years, but a 2012 proposal calls for certificates that remain valid for only four days, eliminating the need for a revocation mechanism (Topalovic et al.).

Indication and Interpretation of Trust

When a user browses to a website, they are expected to verify that they are connecting over HTTPS. This is indicated to the users through the https:// at the beginning of the URL in the address bar, and the green lock icon displayed by the browser. This icon may typically be clicked on to display more information about the website’s certificate. However, studies have shown that many users do not look for these indicators, and may even assume a page is secure based on the type of information being displayed.

Even when a browser displays a warning for a failed HTTPS connection, many users will click through and still log into the site. This may be due to users not understanding the certificate warning, not understanding the risks of visiting a site with an invalid certificate, or making a decision to visit the site anyway despite understanding and weighing the rists. Another common warning is the mixed scripting warnings, indicating that Javascript is being loaded over plain HTTP but being run within the HTTPS site’s privileges.

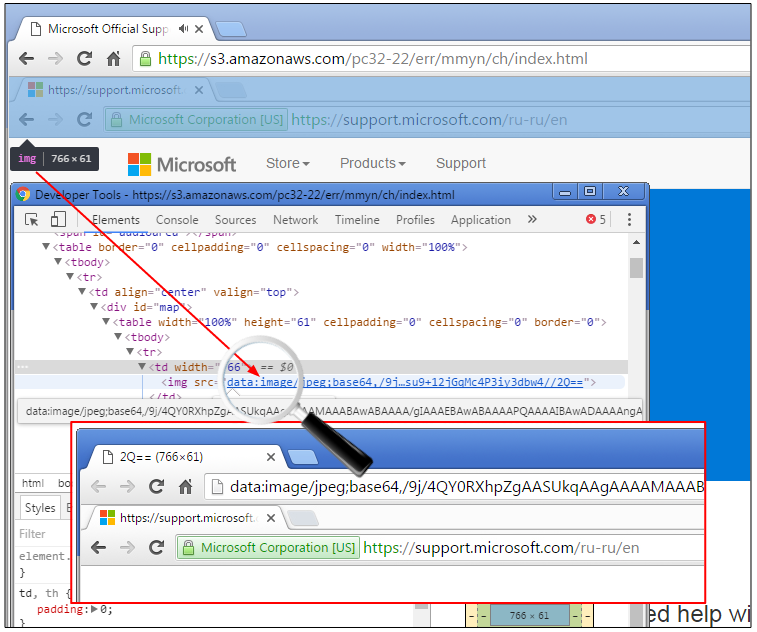

If an adversary expects a user to look for HTTPS indicators, they may be able to spoof common security cues. Some users believe an image of a lock on the website is a sign of a successful HTTPS connections. A more involved example is shown in the image below, where an attacker has simulated a browser address bar, complete with the HTTPS indicators that come with a valid EV certificate.

Fake Address Bar (Image from Malwarebytes)

CONIKS and Certificate Transparency

CONIKS: Bringing Key Transparency to End Users, Marcela S. Melara, Aaron Blankstein, Joseph Bonneau, Edward W. Felten, Michael J. Freedman, USENIX Security ‘15

CONIKS is a key management system intended to reduce the workload on clients to verify keys for secure communications. It’s an extension of the existing certificate transparency logs for webservers to end users. CONIKS simultaneously helps address the issue of service providers tampering with keys and of trust establishment that would otherwise be done out-of-band manually. The system is intended to prevent equivocation of keys, prevent the addition of unauthorized keys, and allow for transparent and public verification all while being efficient for users.

CONIKS is motivated by a desire to increase the use of end-to-end encryption, which has traditionally struggled with key management. Systems like WhatsApp and Apple’s iMessage use centralized storage of public keys which is vulnerable to key removal, key changing, or server takeover. Furthermore, many systems have no way (beyond clunky manual steps) to verify contacts are who they claim to be.

Design

The design of CONIKS involves several non-distinct participants: service providers, end users, and auditors. Service providers manage their own individual namespace of name (e.g., alice@host.com) to key bindings. While not assumed to be trustworthy, service providers are expected to have a reputation to uphold. End-users are the clients and intend to communicate with each other securely. Clients require only a relatively accurate clock and a usable network connection. They are also responsible for serving as auditors who track the key log for forgeries, invalid updates, and new unsolicited keys.

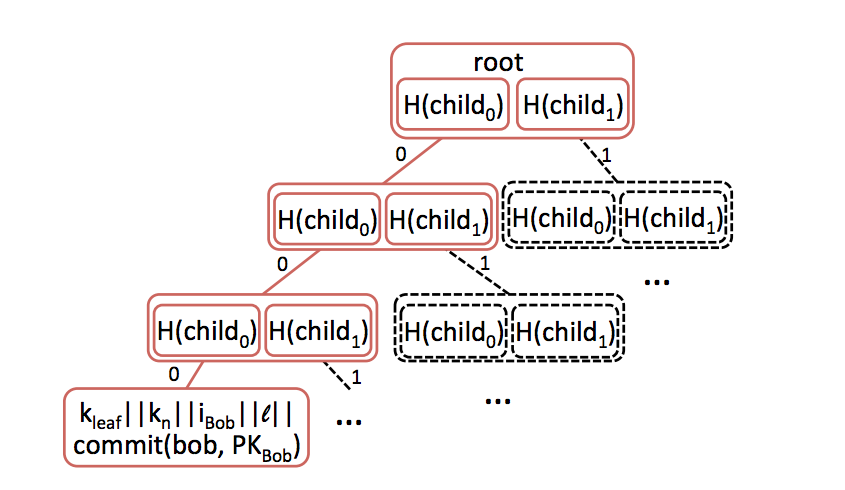

Each service provider constructs its directory of name → key mappings as a Merkle binary prefix tree, with each tree node representing a unique prefix.

Merkle Prefix tree (image from CONIKS paper

As in other Merkle trees, interior nodes represent hashes of their left and right children. Leaf nodes are hashed over a nonce (kn), a node index, the tree depth, and a cryptographic commitment of the user’s name and public key. Empty or placeholder nodes are hashed similarly, but instead include a different constant, kempty.

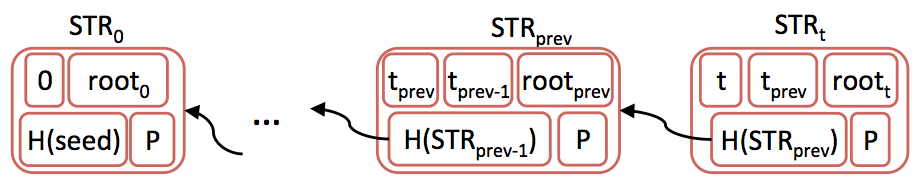

Signed STR chain (Image from CONIKS paper)

At regular intervals, or epochs, the service provider signs the merkle root of the previous tree and a sequentially increasing number to indicate the order of the blocks. This helps ensure that service providers cannot change the historical record easily, and also must maintain a changed STR chain indefinitely.

Common Operations

Registration in a CONIKS system occurs when the user sends their name and public key to the service provider. Since the server only published a signed record every epoch, it will issue a “temporary binding” in the mean-time to validate the key, signing the user key, name, and eventual index.

To look up a key, clients will consult the server for a given name and receive the matching public key and a STS proof of inclusion, consisting of all the hashes from the position of the key on the way up the tree. Since interior nodes consist only of hashes of the left and right nodes, the client can verify that the key is at the position the server claims, or that the key is truly missing if the server claims it is.

A general flow for secure communications therefore looks something like this:

- Alice contacts the service provider (Carol) and requests the public key for

bob@host.com. - Carol returns the public key and the proof of inclusion hash chain.

- Alice computes the merkle root of the tree and compares to her last known root from the STR chain.

- After proving Carol gave the correct key, Alice encrypts her message with Bob’s public key and sends it.

Auditing

One of the most important features of CONIKS is the ability for anyone to audit the name → key mappings. Indeed, clients are encouraged to regularly audit their own keys to ensure they have not been compromised. Auditing works much like key lookup — the server is consulted for the key mapping to the given name. Clients who are also auditing will confirm that the returned private key matches the saved one they possess, and that the keys have not changed in an authorized way between epochs.

Considerations for deploying CONIKS

Initial key submission window

It’s important to note that until the next STR is published, clients won’t be able to communicate using their public key, as nobody else will have seen it. However, clients can audit their own keys to prevent any malicious actors from changing their initial key upload.

‘Whistleblowing’

The CONIKS protocol currently doesn’t provide any way for clients to contact each other if they detect malicious activity either in general or on the part of the service provider. If their keys are hijacked, they are responsible for communicating that information to others on their own, which could be over an unsafe channel.

Key Change or Revocation

CONIKS doesn’t currently provide any way for users to update or revoke their keys directly. One easy path would be for users to sign some message indicating they wish to remove the previous key. However, if a user lost their key they would be unable to revoke their old one.

SSL Stripping

Defeating SSL Using sslstrip 2009 Black Hat DC presentation by Moxie Marlinspike

In this part of the blog post we further explore the sslstrip attack, presented to the class by Team Sesame on February 10th, 2017.

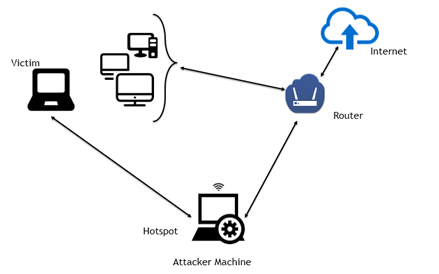

In-the-Middle Attack Setup (Image from avicoder)

Overview

The sslstrip attack is both an in-the-middle attack and protocol downgrade attack that relies on websites not implementing HSTS and also browsers’ inability to prevent users from POST’ing sensitive data to HTTP websites.

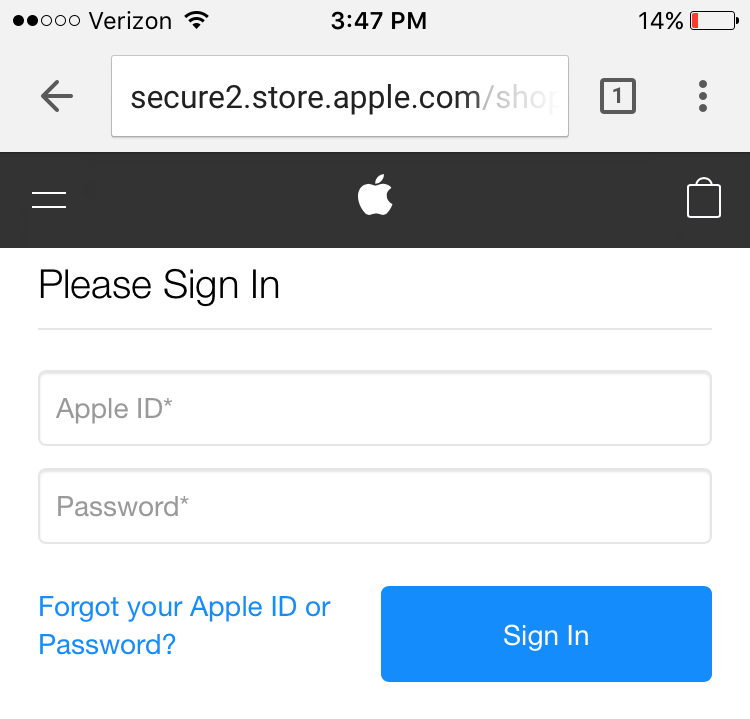

The sslstrip python module, when used in conjunction with an MITM framework, replies to the victim’s HTTPS requests with HTTP versions of the same page silently stripping the S. On modern browsers the only visual cue is the lack of HTTPS:

Screenshot of Chrome on iPhone 7

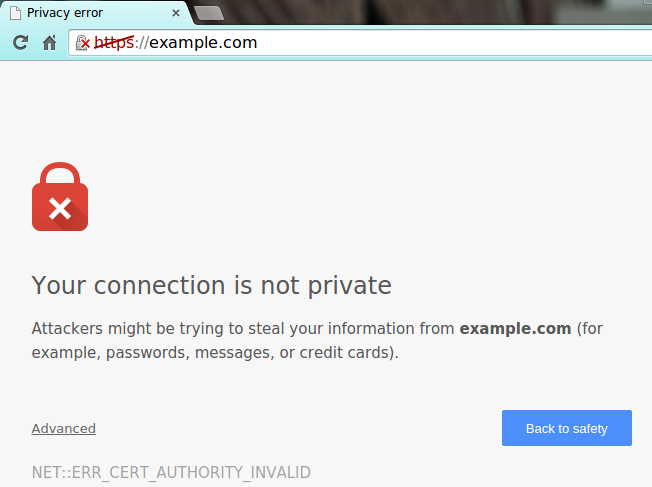

This differs from other HTTPS MITM attacks whereby an attacker forces the victim to connect to a fake access point where tools like mitmproxy can be then used to sign forged certificates for websites on the fly.

However, most browsers have mechanisms to protect against this like HTTP Public Key Pinning (HPKP) and browser warnings:

Self signed SSL certificate warning in Google Chrome, image courtesy of Inmotionhosting.

Necessary Requirements

In order for an attacker to obtain victim credentials for a given HTTPS website using sslstrip

- The attacker must be on the same LAN as the victim (necessary to obtain MITM status)

- The HTTPS website the victim accesses must have initiated the connection first via HTTP

- The given website must not be on victim’s browsers HSTS Preloads (supported by all modern browsers, this list includes the Google domains and ~7500 other sites)

Sslstrip works by listening for HTTP 301 “Moved Permanently” (i.e., Redirect to HTTPS). So unless the victim explicitly types in https:// (HTTPS to begin with) or the website is on the browser’s HSTS Preloads, or the website is HTTPS only, the 301 will be issued and at that point sslstrip will intercept this response and instead relay back to the victim a HTTP version of the HTTPS site.

So, Requirement 2 is necessary for sslstrip to work. In the case of the website being on the browser list of HSTS preloads, then the first request over HTTPS is is never dispatched but rather internally redirected by the browser to the HTTPS version which is why Requirement 3 states the given website must not be on the HSTS Preload list.

Countermeasures

The most obvious countermeasures include:

- Browser Indications, SSLight, other addons?

- Server: HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security) Preloads

- Server: HTTPS only

While improvements have been made to sslstrip such as using different domains like wwww (and various countermeasures like key pinning and browser displays), in present day the original sslstrip (2009) does not work against sites with HSTS enabled like facebook.com and gmail.com. Surprisingly though, a 2016 article claimed only 1 in 20 HTTPS servers implemented HSTS correctly!

Sslstrip is an easily-deployable and effective attack “in the wild” because of but not limited to session hijacking and the fact most browsers do not alert users they are submitting over http (or conversely most users do not notice http:// when submitting sensitive info). In addition, password reuse is widespread and if credentials were obtained from say apple.com or a bank they could be tried against more sensitive websites which do support HSTS (enable two factor authentication!!).

Further Reading:

Writeup describing modern browser and website protections against MITM attacks:

https://www.troyhunt.com/understanding-http-strict-transport/

Try it out yourself! This blog post describes how an attacker on Mac OS X could use sslstrip to gather credentials over network. I learned both my online banking website and apple.com were vulnerable to sslstrip (i.e. the domains of these sites were not on my browsers HSTS preload list).

http://techjots.blogspot.com/2012/11/sslstrip-on-mac-os-x-mountain-lion.html