TLS 1.3

TLS Evolves: Version 1.3

TLS v1.3 is a major revision to TLS to simplify the protocol, and improve its security and performance. In order to get a good understanding of TLS v1.3 and where it is heading in the future, we will first look at where TLS has been.

Looking Backward: Retro TLS

SSL/TLS has a storied past. SSL v1.0 was never released. Netscape, the company that originally developed SSL, circulated it internally but decided not to release it to the public because it had several flaws including a lack of data integrity protection.

After that non-starter, the timeline looks like this:

- 1994: Netscape develops SSL v2.0 which is shipped with the Netscape Navigator 1.1

- 1995: SSL v2.0 has serious security issues; Netscape releases SSL v3.

- 1999: TLS v1.0 released; standardizing and upgrading SSL v3.0

- 2006: TLS v1.1 released; address the BEAST attack, which will come in 5 years

- 2008: TLS v1.2 released with Authenticated Encryption

- 2011: Google deploys public key pinning and forward secrecy

- 2013: Work on TLS v1.3 begins

A more thorough timeline can be found at SSL/TLS and PKI History.

So what does TLS v1.3 bring to the table? Let’s take a look…

Faster Handshake

TLS 1.3 introduces a significantly slimmer Handshake Protocol than previous versions. In order to understand the implications of these changes, we first review the Handshake Protocol used in TLS 1.2.

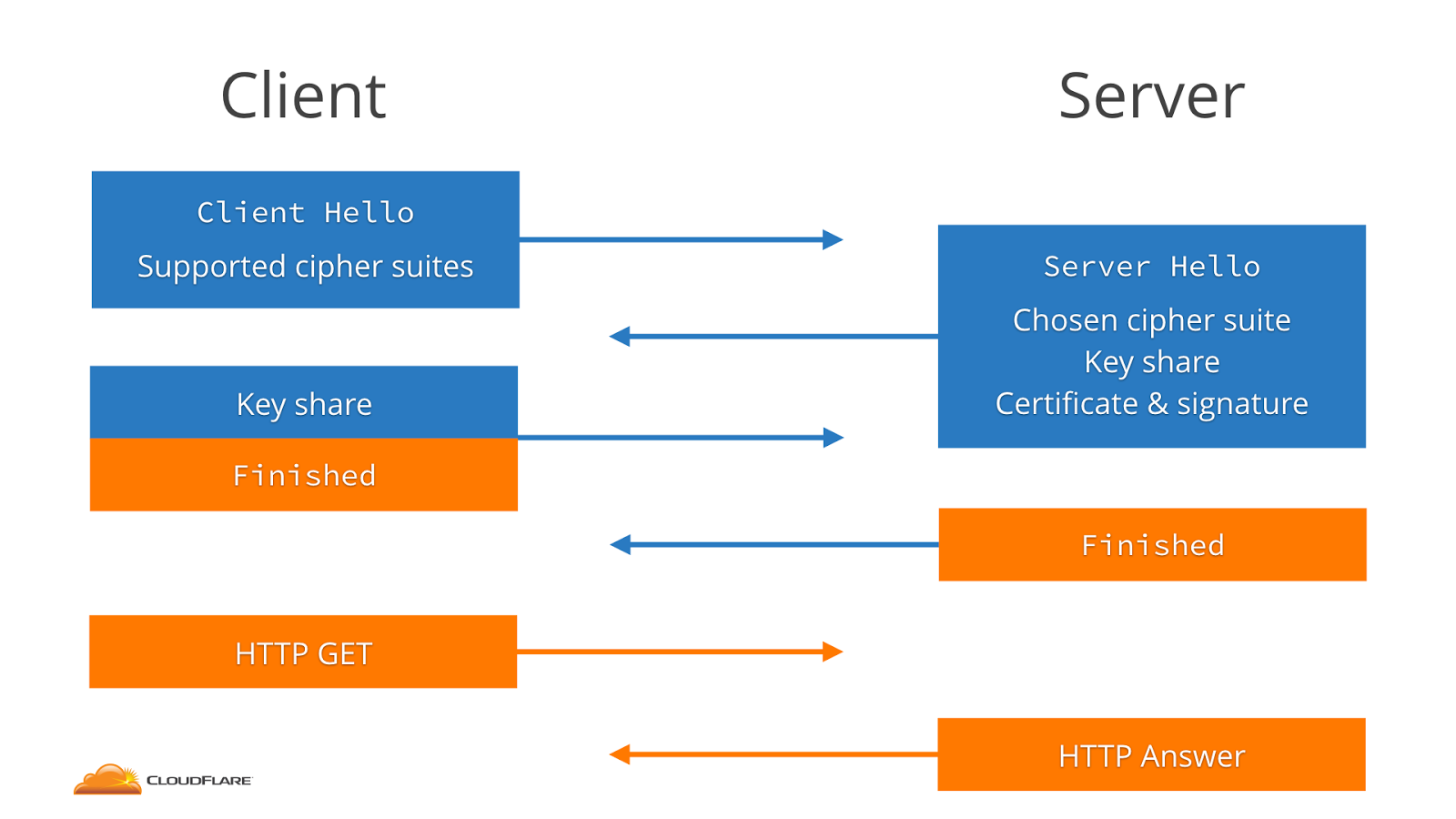

In TLS 1.2, the client begins the handshake with a Client Hello,

followed by a Server Hello response from the server. The client then

proceeds with a Client Key Exchange and Client Finished; the

server responds with its own versions of these messages.

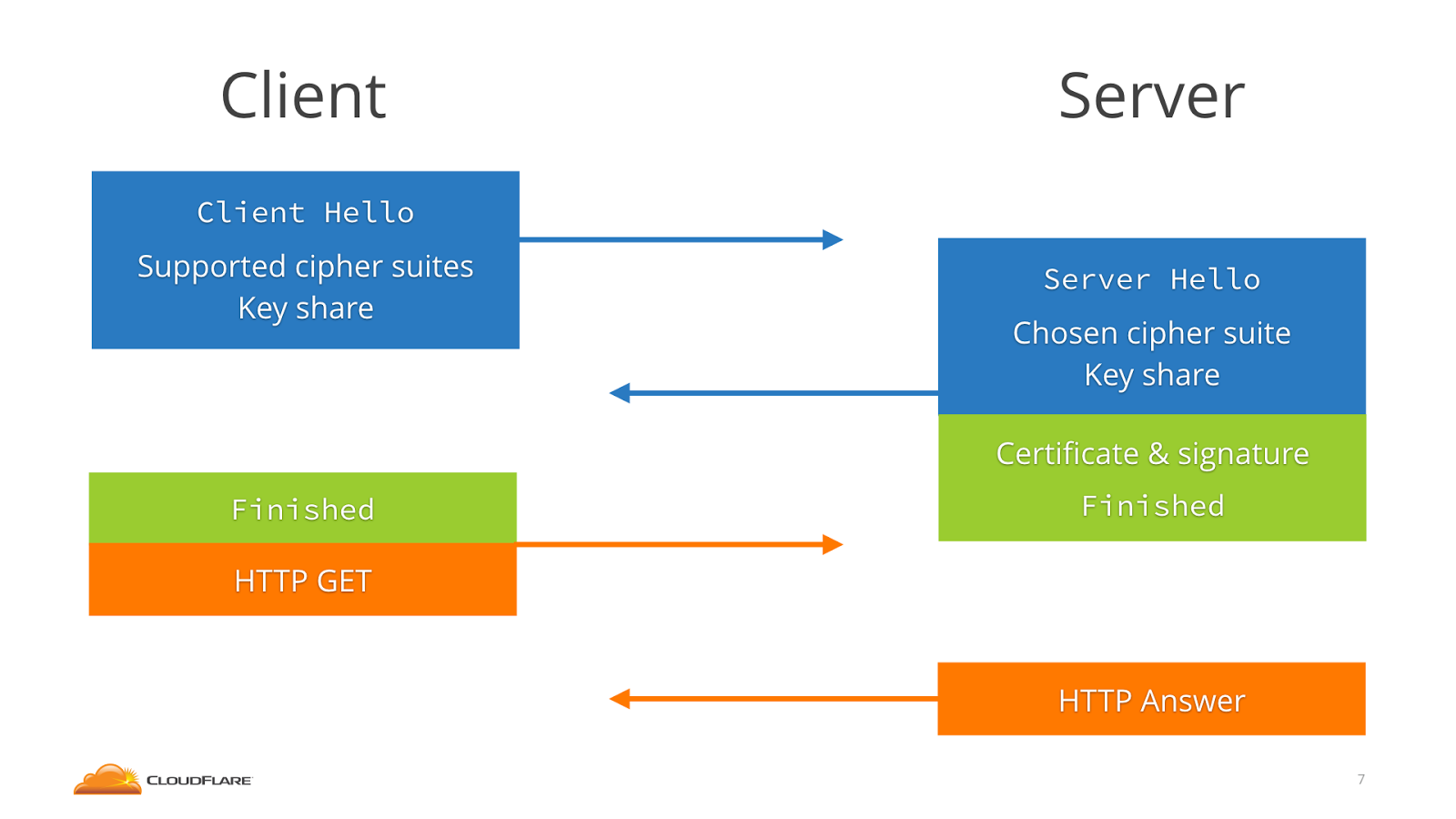

In contrast, TLS 1.3 incorporates the key share messages with the

Client/Server Hello, meaning that each side of the connection has to

send one less message (and only send one message total to initiate the

connection).

TLS 1.2 Handshake

TLS 1.3 Handshake

Sidebar: AuthLoop

AuthLoop: End-to-End Cryptographic Authentication for Telephony over Voice Channels, Bradley Reaves, Logan Blue, and Patrick Traynor. USENIX Security Symposium. August 2016.

On the subject of modification and adaptations to the typical TLS 1.2 system of encryption and authentication, we explore AuthLoop: a TLS-style authentication protocol specifically designed for telephony networks. In this domain, the system must connect three different types of telephony networks: cellular, VoIP, and PSTN. However, the TLS Handshake transmission speeds for such a system were extremely slow - averaging 98 seconds per handshake - which is completely infeasible for most phone calls. AuthLoop keeps the authentication and shared secret elements of TLS and a freshness/liveness component analogous to the Heartbeat Protocol. On the other hand, AuthLoop removes RSA and the cipher agreement messages. Furthermore, AuthLoop does not encrypt messages and therefore has no Record Protocol. After slimming down, the average transmission time reduced drastically to 4.8 seconds.

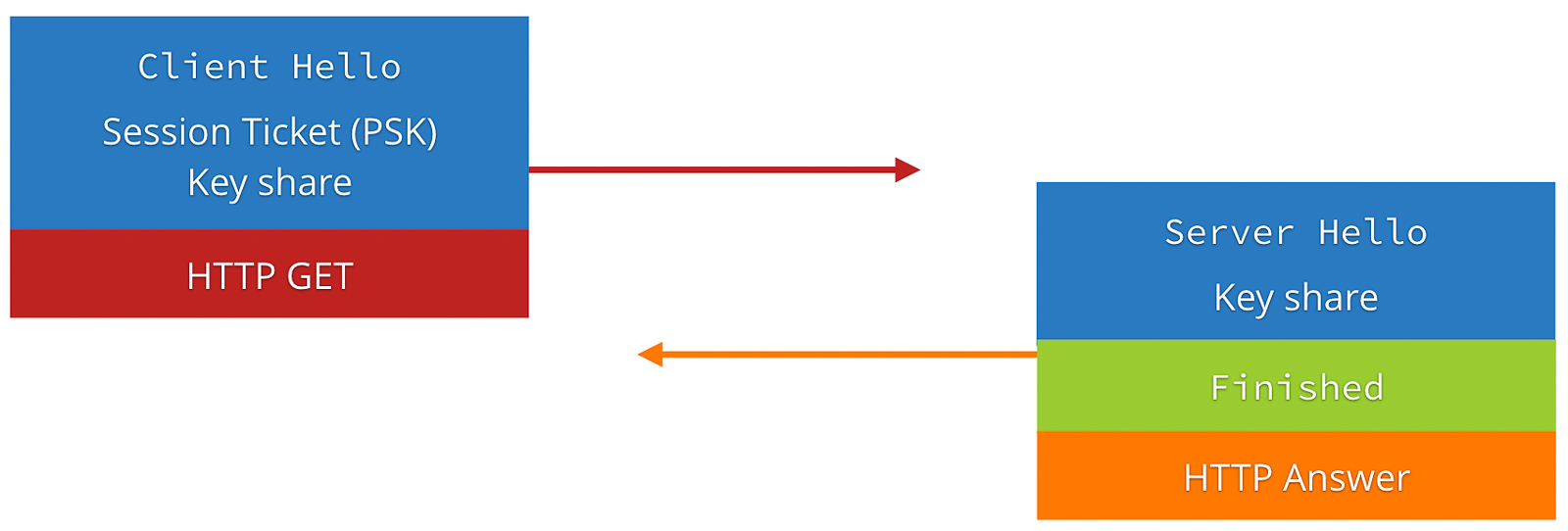

0-RTT Resumption

A major new feature in the TLS 1.3 draft is support for 0-RTT session resumption. In TLS 1.2, establishing a connection to a new server required at least 4 trips between the server and client to make an HTTP request and receive a response. With a session-ID or session ticket, that could be reduced to 3 trips per connection. TLS 1.3 by default reduces the number for new connections to only 3 trips per connection, but also adds support for a new mode termed 0-RTT. In this mode, resumed HTTPS connections require only 2 trips, which is the bare minimum required for a full HTTP query and response. In this mode, TLS 1.3 adds barely any additional latency cost over a plain HTTP request!

TLS 1.3 0-RTT (Source: https://blog.cloudflare.com/tls-1-3-overview-and-q-and-a/)

However, the addition of 0-RTT resumption to the protocol has an important implication for the security features provided by the protocol. Because TLS 1.3 session tickets, which enable 0-RTT resumption, are stateless on the server, such requests from the client are trivially vulnerable to replay attacks. An attacker who can intercept an encrypted client message can re-send it to the server, tricking the server into processing the same request twice (which could be serious, for example, if the request is “transfer $x to Bob”).

To remedy this, the protocol authors recommend that initial requests from the client be idempotent, or non-state-changing. Servers should not allow the first request to be idempotent in 0-RTT mode. This has been arguably the most controversial part of the new standard, as it puts the onus on some higher level protocol to solve a problem that TLS has historically been responsible for. Even worse, it is not solved directly by HTTP but rather must be specifically kept in mind by web developers.

Deployment

Deployment of TLS 1.3 remains loosely in the future as the protocol specification finishes its final draft. Current TLS 1.3 drafts include 0-RTT by requiring servers to set up a profile that defines its use. However, as with many other features in earlier TLS protocols, 0-RTT data is not compatible with older servers. A server using TLS 1.3 has the option to limit what early data to use in a 0-RTT and what to buffer.

Data Center use of Static Diffie-Hellman: While ephemeral (EC) Diffie-Hellman is in nearly all ways an improvement over the TLS RSA handshake, it has a limitation in certain enterprise settings. Specifically, the use of ephemeral (PFS) ciphersuites is not compatible with enterprise network monitoring tools such as Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) that must passively monitor intranet TLS connections made to endpoints under the enterprise’s control. Such monitoring is ubiquitous and indispensable in some industries, and loss of this capability may slow adoption of TLS 1.3.

Deployment of TLS 1.3 across the web faces several industry concerns, most notably regarding Static RSA (no forward secrecy), as posted from an email exchange between Andrew Kennedy, an employee at BITS (the technology policy division of the Financial Services Roundtable http://www.fsroundtable.org/bits), and Kenny Paterson.

Andrew Kennedy writes,

… While I am aware and on the whole supportive of the significant contributions to internet security this important working group has made in the last few years I recently learned of a proposed change that would affect many of my organization’s member institutions: the deprecation of RSA key exchange.

Deprecation of the RSA key exchange in TLS 1.3 will cause significant problems for financial institutions, almost all of whom are running TLS internally and have significant, security-critical investments in out-of-band TLS decryption.

Like many enterprises, financial institutions depend upon the ability to decrypt TLS traffic to implement data loss protection, intrusion detection and prevention, malware detection, packet capture and analysis, and DDoS mitigation.

Kenny’s response: (excerpted from https://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/tls/current/msg21278.html)

Hi Andrew,

My view concerning your request: no.

Rationale: We’re trying to build a more secure internet.

Meta-level comment:

You’re a bit late to the party. We’re metaphorically speaking at the stage of emptying the ash trays and hunting for the not quite empty beer cans.

More exactly, we are at draft 15 and RSA key transport disappeared from the spec about a dozen drafts ago. I know the banking industry is usually a bit slow off the mark, but this takes the biscuit.

Cheers,

Kenny

Anti-Downgrade Prevention and Detection

Downgrade resilience in key-exchange protocols by Karthikeyan Bhargavan, Christina Brzuska, Cédric Fournet, Markulf Kohlweiss, Santiago Zanella-Béguelin and Matthew Green in IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 2016.

TLS 1.2 suffers from various downgrade and man-in-the-middle attacks like Logjam, FREAK and POODLE. Logjam exploits the option of using legacy “export-grade” 512-bit Diffie–Hellman groups in TLS 1.2. It forces susceptible servers to downgrade to cryptographically weak 512 bit Diffie-Hellman groups, which could then be compromised. FREAK is a man-in-the-middle attack that affects the OpenSSL stack, the default Android web browser, and some Safari browsers. It tricks servers into negotiating a TLS connection using cryptographically weak 512 bit encryption keys. POODLE exploits vulnerability in SSL 3.0 but is applicable to TLS 1.2 once the attacker performs version rollback to SSL 3.0 through a man-in-the-middle attack.

The above problems can be countered using correct downgrade protection. While TLS 1.2 does implement downgrade protection, it fails to do so correctly. Downgrade protection requires sending MAC of finished messages between client and server to ensure that the negotiated parameters have not be modified by a MITM attacker. TLS 1.2 does not hash all the negotiated parameters in its MAC allowing the attacker to alter the non-hashed parameters and launch downgrade attacks. TLS 1.3 fixes this issue by hashing all the parameters and also isolates TLS 1.2 or lower version messages (which have downgrade resilience issues) by requiring the TLS 1.3 server to set first N bits of its ServerRandom nonce to a fixed value on recieving ClientHello message from a TLS 1.2 or below client. This signals the TLS 1.3 clients and they reject any packet that has the fixed value sequence.

Downgrade Resilience in Key-Exchange Protocols

Downgrade protection primarily relies on the MACs in the finished messages, which in turn rely on the strength of the group and the negotiated algorithms and hash. If a client and server support a weak group, then an attacker can downgrade the group and break the master secret to forget the MACs, as in Logjam.

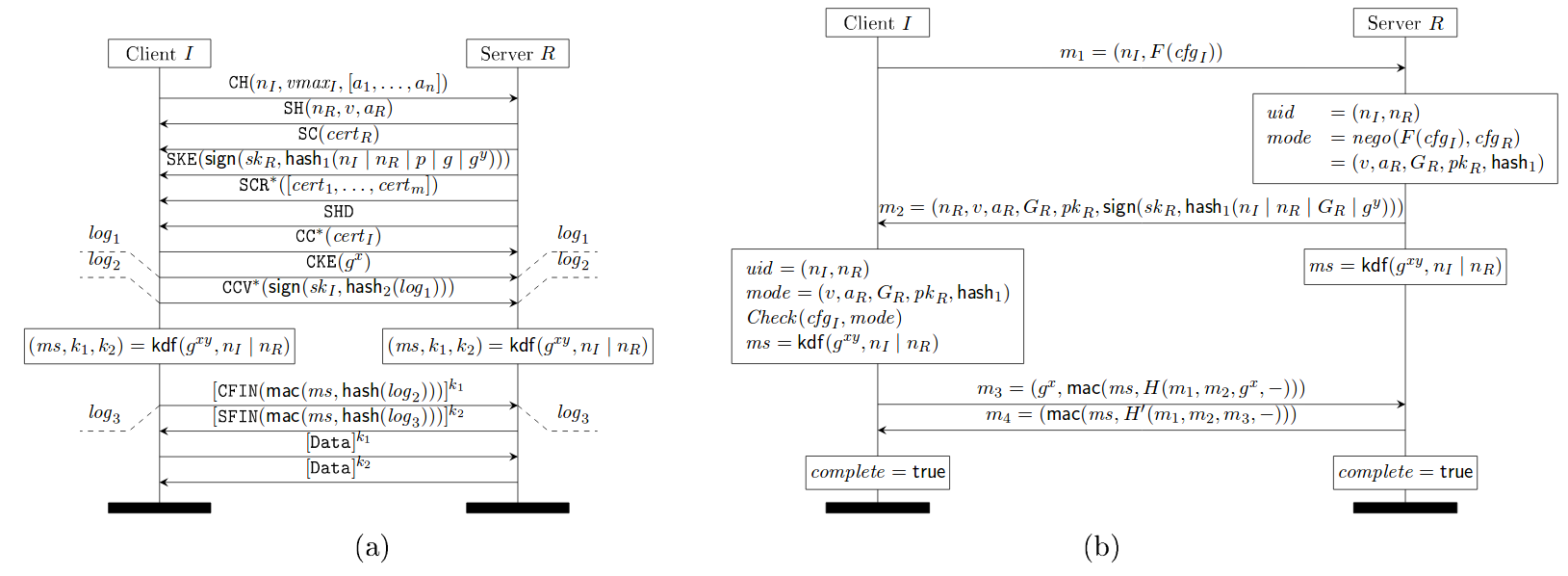

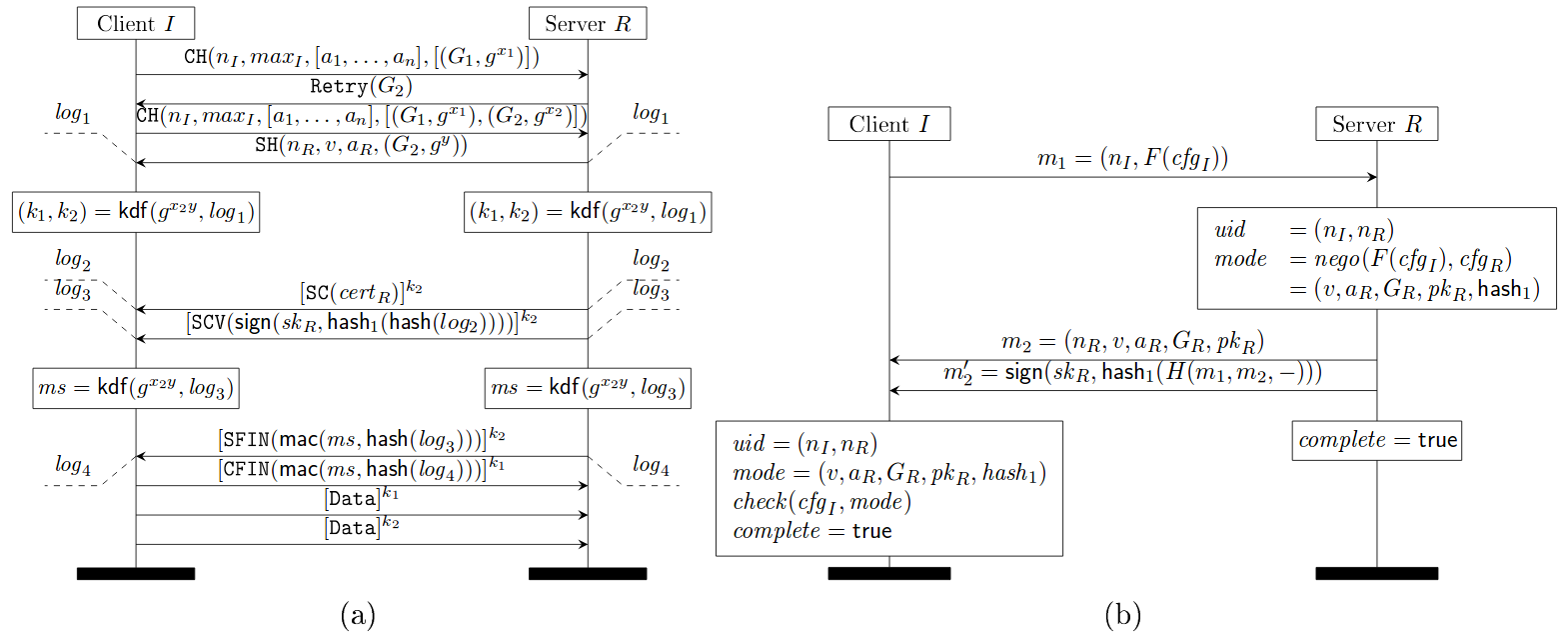

The figure below shows the faulty downgrade resilience of TLS 1.2, where the TLS 1.2 server fails to hash the negotiated parameters like protocol version (v), chosen parameters (a_R) and server identity (pk_R) in its hash message hash_1(.) (see subfigure (b) of the below figure).

TLS 1.0 - 1.2 with (EC)DHE key exchange (a), where messages labeled with * occur only when client authentication is enabled, and (b) its downgrade protection sub-protocol

Source: https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/072.pdf

Draft 10 of TLS 1.3 implements the following downgrade protection mechanism which rectifies the above mistake and consequently hashes all the negotiated parameters. Notice the hash_1(H(m_1, m_2, -)) in the message sent by server (subfigure (b) in the figure below), which hashes all the negotiated parameters in m_2.

TLS 1.3 1-RTT mode with server-only authentication (a) and its downgrade protection sub-protocol (b)

Source: https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/072.pdf

However, there are three downgrade attacks possible on TLS 1.3 as described in Draft 10. One, an attacker downgrades the connection to TLS 1.2 or lower and mounts any of the downgrade attacks mentioned before. This will succeed as long as the attacker can forge the finished MACs. Second, an attacker uses the TLS fallback mechanism to stop TLS 1.3 connections and allows only TLS 1.2 connections to go through. Even if the end points implement the fallback protection mechanism, the attacker can use one of the downgrade attacks in TLS 1.2 to break the connection. Third, in Draft 10 of the TLS1.3 protocol, the handshake hashes restart upon receiving a Retry message and hence, the attacker can downgrade the Diffie-Hellman group for some classes of negotiation functions.

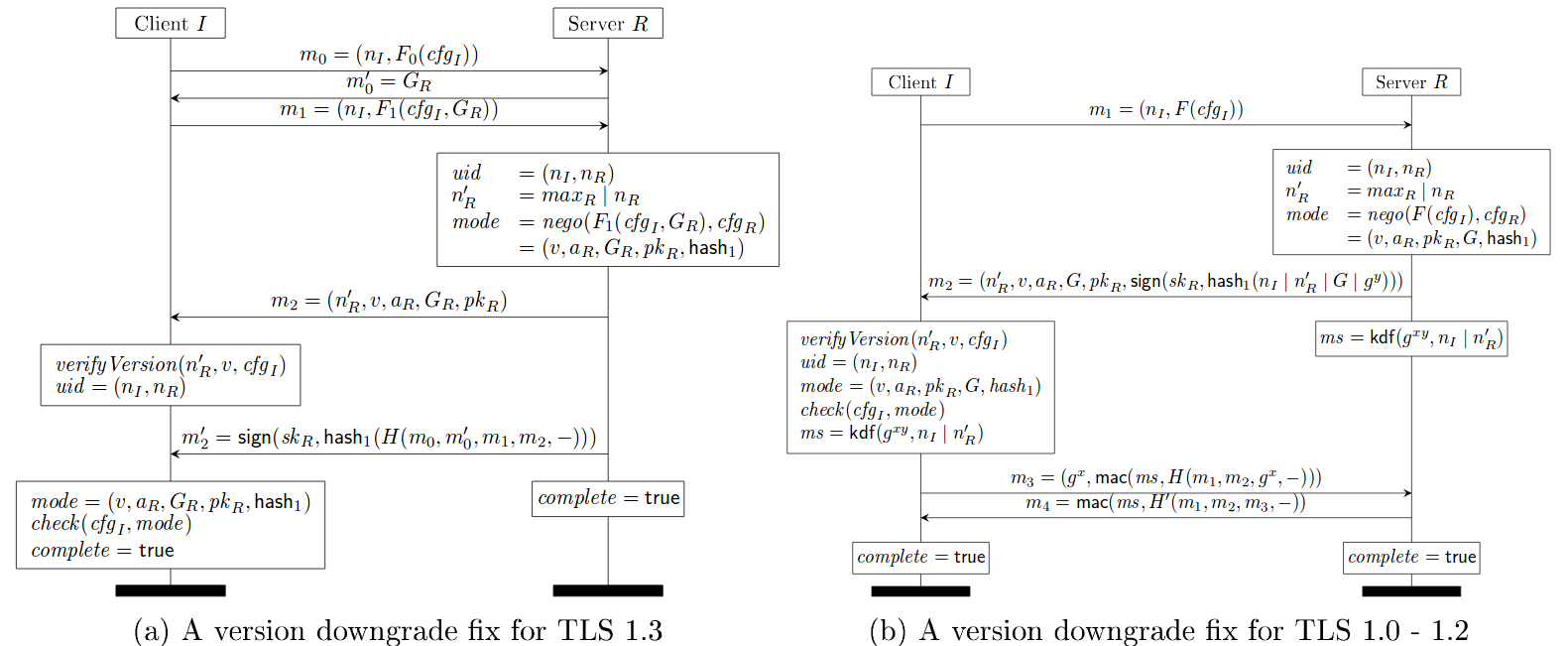

TLS 1.3 draft 11 counters the above three attacks by incorporating two countermeasures.

First, TLS 1.3 protocol continues the handshake hashes over retries (subfigure (a) of the figure below).

Second, TLS 1.3 servers always include their highest supported version number in the server nonce, even when they choose a lower version such as TLS 1.0.

Draft 11 of TLS 1.3 fixed the issue by requiring TLS 1.3 server to set top N bits of the ServerRandom to be a specific fixed value on receiving ClientHello message from a TLS 1.2 or below client. TLS 1.3 clients which receive a TLS 1.2 or below ServerHello check for this value and abort if they receive it. The figure below shows the client check using verifyVersion functionality.

This allows for detection of downgrade attacks over and above the Finished handshake as long as ephemeral cipher suites are used. This prevents attacks targeted at (EC)DHE.

TLS 1.3 Draft 11 Update on Downgrade Resilience in Key-Exchange Protocols

Source: https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/072.pdf

The TLS 1.3 server will send a ServerHello message in response to a ClientHello message when it is able to find an acceptable set of algorithms and the client’s key_share extension is acceptable. If it is not able to find an acceptable set of parameters, the server will respond with a handshake_failure fatal alert. The ServerHello message contains server’s random value which incorporates downgrade protection mechanism. If a ClientHello indicates only support for TLS 1.2 or below, then the last eight bytes of server’s random value MUST be set to: 44 4F 57 4E 47 52 44 01.

If a ClientHello indicates only support for TLS 1.1 or below, then the last eight bytes of server’s random value SHOULD be set to: 44 4F 57 4E 47 52 44 00.

TLS 1.3 clients are required to check the above values in the random field of server responses.

Authenticated Encryption

Up until now, we’ve mostly concerned ourselves with the “MAC-Encode-Encrypt” (MEE) packet construction method. In a nutshell, MEE follows three steps:

- Calculate a MAC over the payload

- Append the MAC and an appropriate amount of padding to the payload

- Encrypt the modified payload to generate a ciphertext

As we’ve discussed in previous classes, the CBC mode of operation has its downsides; adversaries can break encryption by utilizing padding oracle attacks, since padding can only exist in a handful of values and lengths. Moreover, it’s impossible to actually verify the integrity of the ciphertext until the MAC has been revealed by decrypting the ciphertext. The duration required to decrypt the tampered ciphertext and validate the MAC leaks sensitive (and potentially useful) timing information to adversaries.

Encrypt-then-MAC

In general, MEE is inferior to its cousin, “Encrypt-then-MAC” (ETM). In ETM, as opposed to MEE, the plaintext is encrypted before the MAC is calculated. Intuitively, it makes sense that ETM is more secure—any tampering of the ciphertext is immediately evident when the MAC is calculated, therefore no decryption takes place (and no timing information is leaked). Additionally, assuming the ciphertext appears random, the MAC also appears random and reveals no information about the underlying ciphertext.

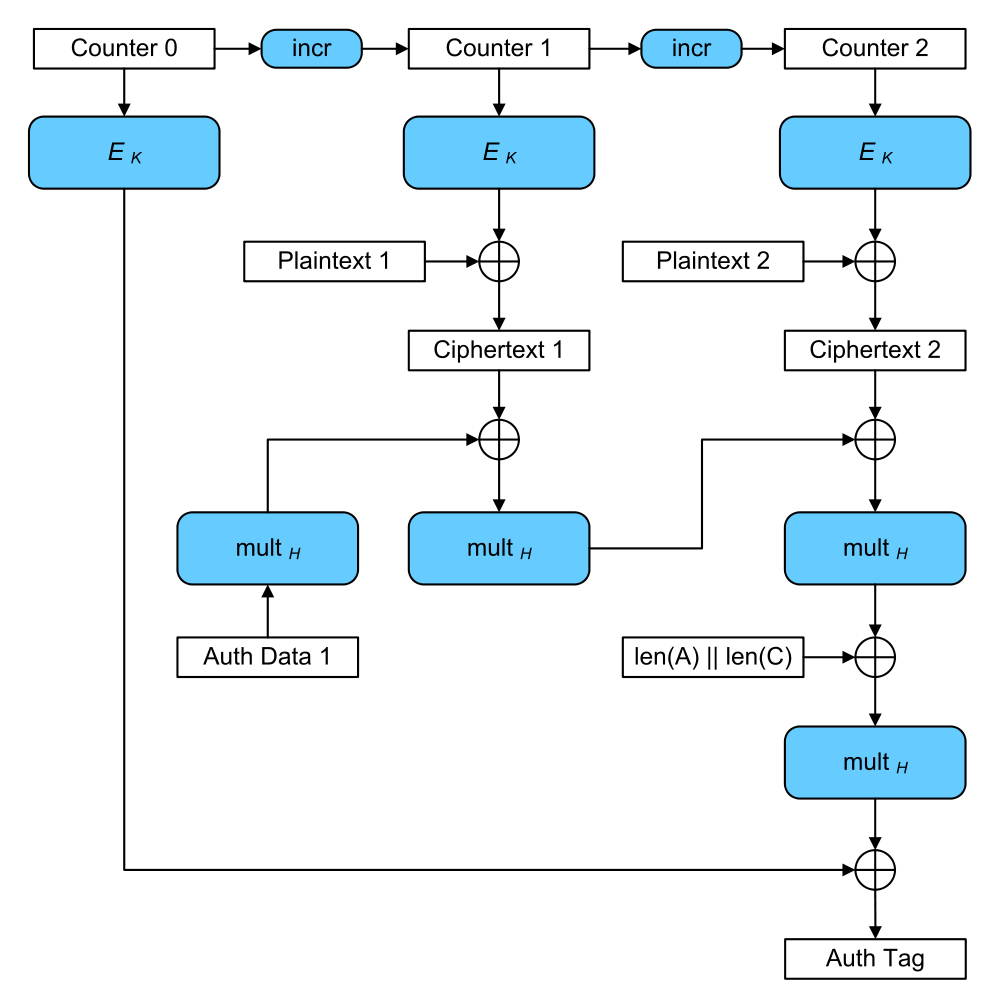

Galois/Counter Mode (GCM)

Before we jump on the ETM bandwagon, however, let’s take a look at yet another mode of operation, Galois/Counter Mode (GCM). GCM is an authenticated encryption algorithm that provides confidentiality and integrity, and does so extremely efficiently.

Galois/Counter Mode (credit: Wikipedia)

GCM At-A-Glance

- Sequentially number blocks

- Encrypt block numbers with block cipher E

- XOR result of encryption with plaintext to produce ciphertext

- Combine ciphertext with authentication code to produce authentication tag

The authentication tag can be used to verify the integrity of the data upon decryption, similar to an HMAC. If this “counter mode” of authenticated encryption seems superior, that’s because it is! TLS 1.3 only provides support for GCM, CCM, and ChaCha20-Poly1305, another authenticated encryption mode of operation. Say goodbye to MAC-then-encrypt.

TLS v1.3 Removals

An overview of TLS 1.3 and Q&A

In TLS v1.3, everything was scrutinized for being really necessary and secure, and scrapped otherwise. In particular, the following things are removed:

- static RSA handshake

- the CBC MAC-then-Encrypt modes, which were responsible for Vaudenay, Lucky13, POODLE, LuckyMinus20

- weak primitives like RC4, SHA1, MD5

- compression

- renegotiation

- custom FFDHE groups

- RSA PKCS#1v1.5

- explicit nonces

Formal Verification

TLS 1.3 is the first revision of the TLS protocol to incorporate formal verification during development. Cas Cremers, Marko Horvat, Sam Scott, and Thyla van der Merwe’s paper, Automated Analysis of TLS 1.3: 0-RTT, Resumption and Delayed Authentication, provides a recent (February 2016) description of the challenges and results of such an analysis. In the blog post associated with their work, the authors contextualize their verification efforts:

The various flaws identified in TLS 1.2 and below, be they implementation- or specification-based, have prompted the TLS Working Group to adopt an “analysis-before-deployment” design paradigm in drafting the next version of the protocol. After a development process of many months, the TLS 1.3 specification is nearly complete. In the spirit of contributing towards this new design philosophy, we model the TLS 1.3 specification using the Tamarin prover, a tool for the automated analysis of security protocols.

The authors are able to prove that revision 10 of the specification meets the goals of authenticated key exchange for any combination of unilaterally or mutually authenticated handshakes. Further, the authors discovered a new, unknown attack on the protocol during a PSK-resumption handshake. The 11th revision of the protocol included a fix for this attack.

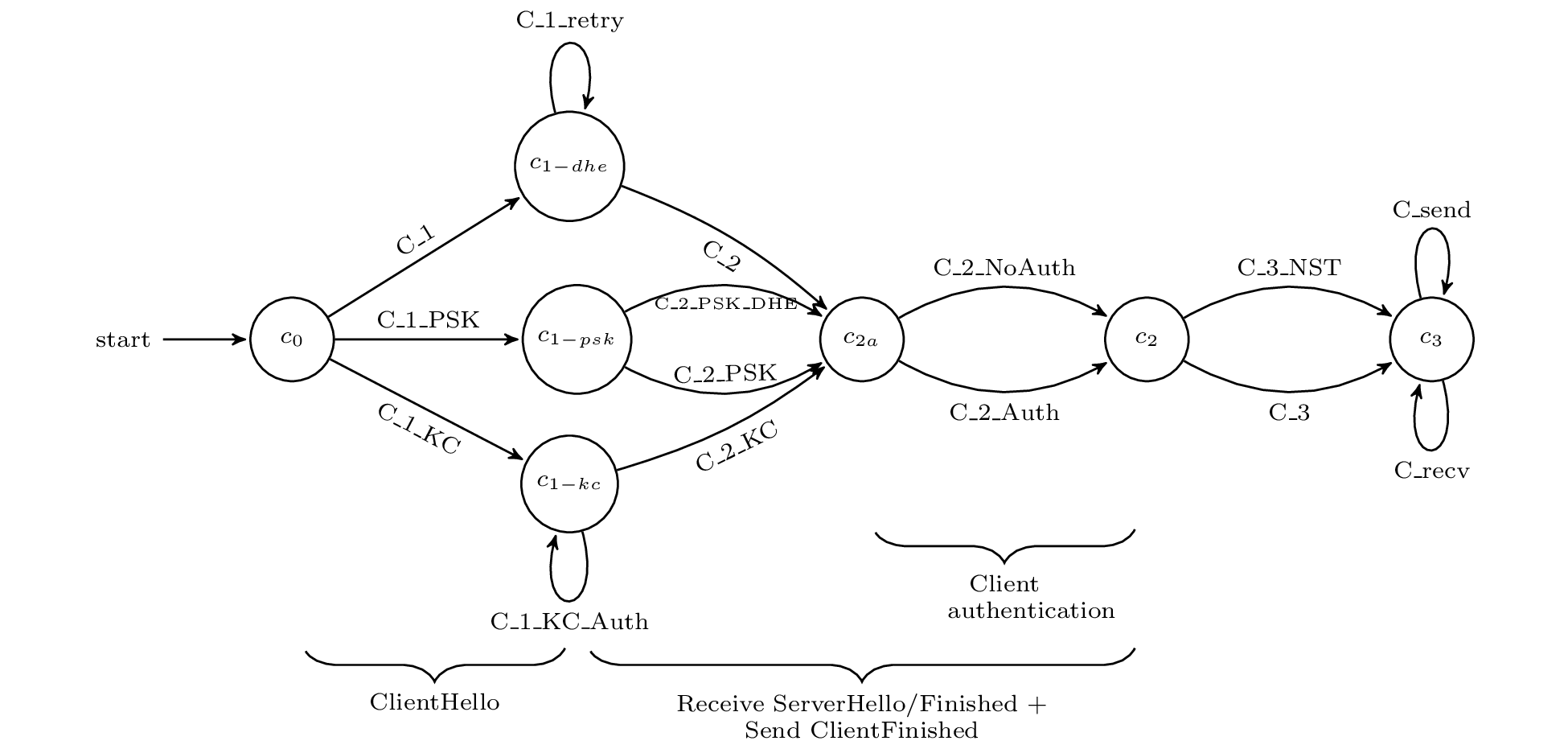

Protocol Model

The authors used the Tamarin prover for their analysis. Tamarin is an interactive theorem proving environment (similar to Coq) specially designed for the verification of protocols such as TLS. As TLS is already an abstract specification, encoding TLS 1.3 into the Tamarin specification language was relatively straightforward. “Rules” (functions) over this specification captured honest-party and adversary actions alike. The following state diagram depicts the client TLS state (as defined in Tamarin) and transitions between the states (Tamarin rules) for an entire session.

Source: Automated Analysis of TLS 1.3

Proven Security Properties

The next step in the analysis involved encoding the desired security properties of TLS 1.3 as Tamarin lemmas. The authors encoded the following properties:

- unilateral authentication of the server (mandatory)

- mutual authentication (optional)

- confidentiality and perfect forward secrecy of session keys

- integrity of handshake messages

Each lemma must hold over its respective domain of states (a subset of the nodes in the client state machine above, for example). While proof assistants like Tamarin are capable of constructing simple proofs, a significant amount of manual effort was required to prove the enumerated lemmas. As such, a notable contribution of this work is the actual Tamarin proof artifact itself, not just what was and wasn’t proven. The authors claim their Tamarin abstractions and proofs were constructed with extensibility to future TLS development in mind.

Discovered Attack

While verifying the delayed authentication mechanism portion of the protocol, an attack was discovered which violated client authentication; an adversary is able to impersonate a client while communicating with the server.

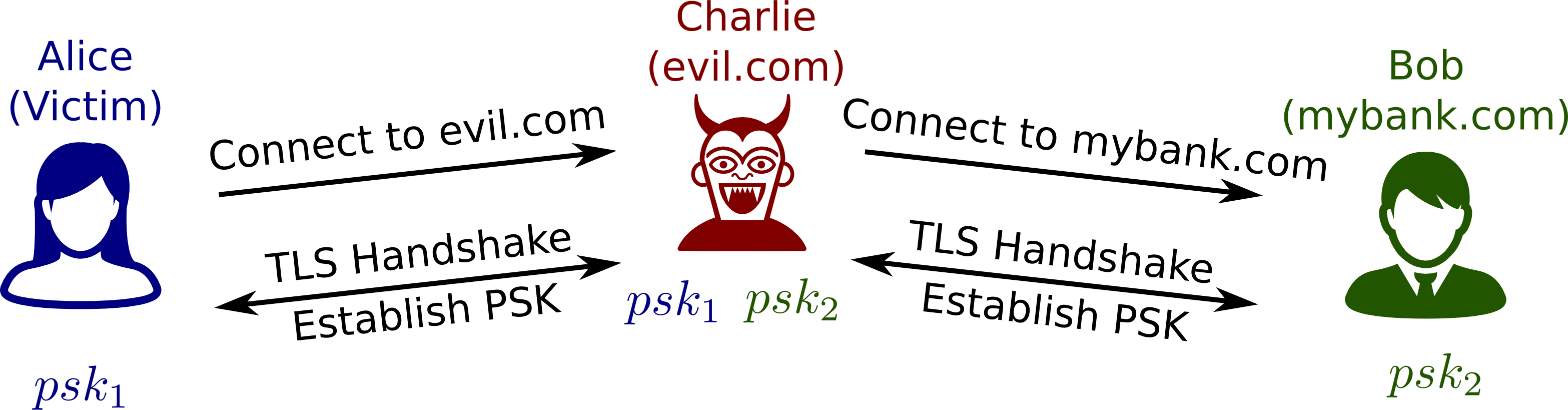

Step 1. The victim client, Alice, establishes a connection with the man-in-the-middle attacker, Charlie. Charlie establishes a connection with Bob, the server which which Alice wishes to connect. A PSK is established for both connections, PSK_1 and PSK_2, respectively.

Source: Automated Analysis of TLS 1.3

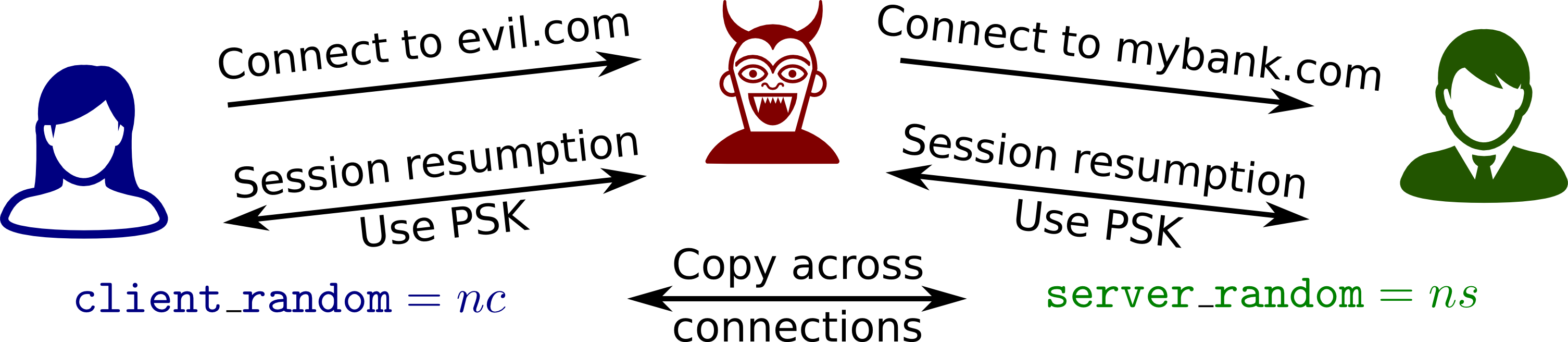

Step 2. Alice sends a random nonce, nc, to Charlie using PSK_1. Charlie reuses this nonce to initiate a PSK-resumption handshake with Bob. Bob responds with random nonce ns and the server Finished message using PSK_2. Charlie reuses ns and recomputes the Finished message for Alice using PSK_1. Alice Returns her Finished message to Charlie. Charlie then recomputes this Finished message for Bob using PSK_2.

Source: Automated Analysis of TLS 1.3

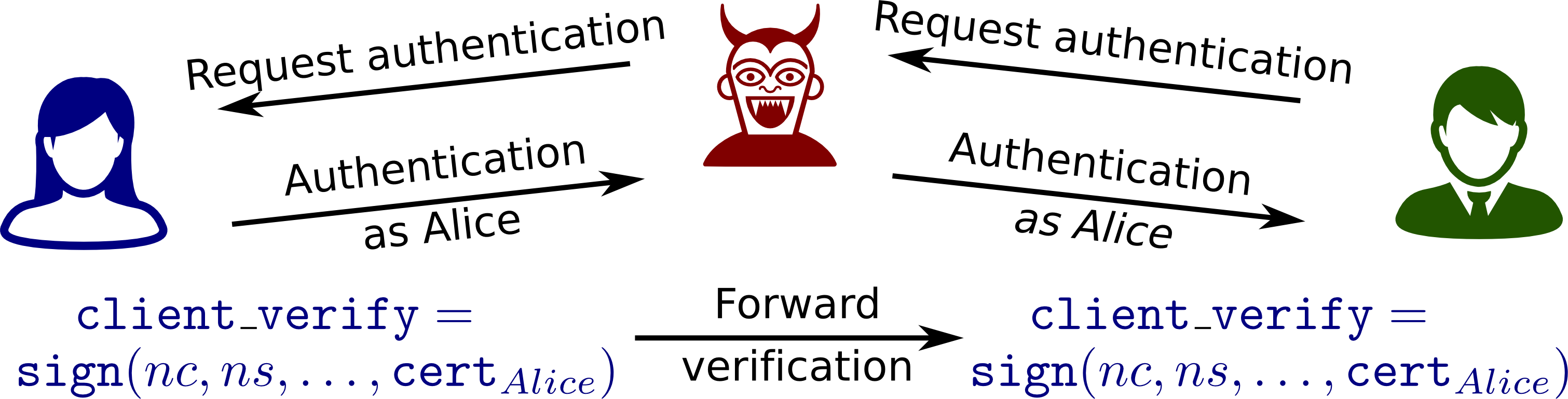

Step 3. Charlie makes a request to Bob that requires client authentication. Charlie is thus prompted for his certificate and verification. This request is re-encrypted and forwarded to Alice. To compute the verification signature of this forwarded request, Alice uses the session_hash value, which is the hash of all handshake messages excluding the Finished messages. This session_hash value will match that of Charlie and Bob’s, and thus Charlie can re-encrypt Alice’s signature for Bob. Bob accepts Alice’s certificate and verification as valid authentication for Charlie.

Source: Automated Analysis of TLS 1.3

The discovery of this attack is noteworthy in that it was completely unexpected by the TLS Working Group.

The fix, which forces the session_hash value to include Finished messages was even suggested in an official pull request, but was rejected.

The authors make a strong case that formal verification has been an extremely valuable part of the design process of TLS 1.3. The speed with which the fix was incorporated into subsequent protocol revisions suggests that the TLS Working Group shares this sentiment.

Two Oakland 2017 papers provide more reports on formal verification efforts for TLS 1.3, up through Draft 18:

- Karthikeyan Bhargavan, Bruno Blanchet, and Nadim Kobeissi. Verified Models and Reference Implementations for the TLS 1.3 Standard Candidate. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, May 2017.

- Karthikeyan Bhargavan, Antoine Delignat-Lavaud, Cédric Fournet, Markulf Kohlweiss, Jianyang Pan, Jonathan Protzenko, Aseem Rastogi, Nikhil Swamy, Santiago Zanella-Béguelin, and Jean Karim Zinzindohoué. Implementing and Proving the TLS 1.3 Record Layer. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, May 2017.